The UK government’s official climate advisers are now “more optimistic” that the country can hit its emissions targets than they were before the Labour government was elected in July 2024.

Speaking ahead of the launch of the Climate Change Committee’s 2025 progress report, Prof Piers Forster, the CCC’s interim chair, told journalists it would be “possible” to meet the UK’s 2030 international climate goal, as well as its 2050 target to cut emissions to net-zero.

Moreover, Forster responded to attacks on climate policy from opposition parties, the Conservatives and Reform UK, by saying that reaching net-zero would, “ultimately, be good for the UK economy”.

The CCC’s report points to progress in areas such as windfarm planning rules, plans for clean power by 2030 and the accelerating adoption of clean-energy technologies for heat and transport.

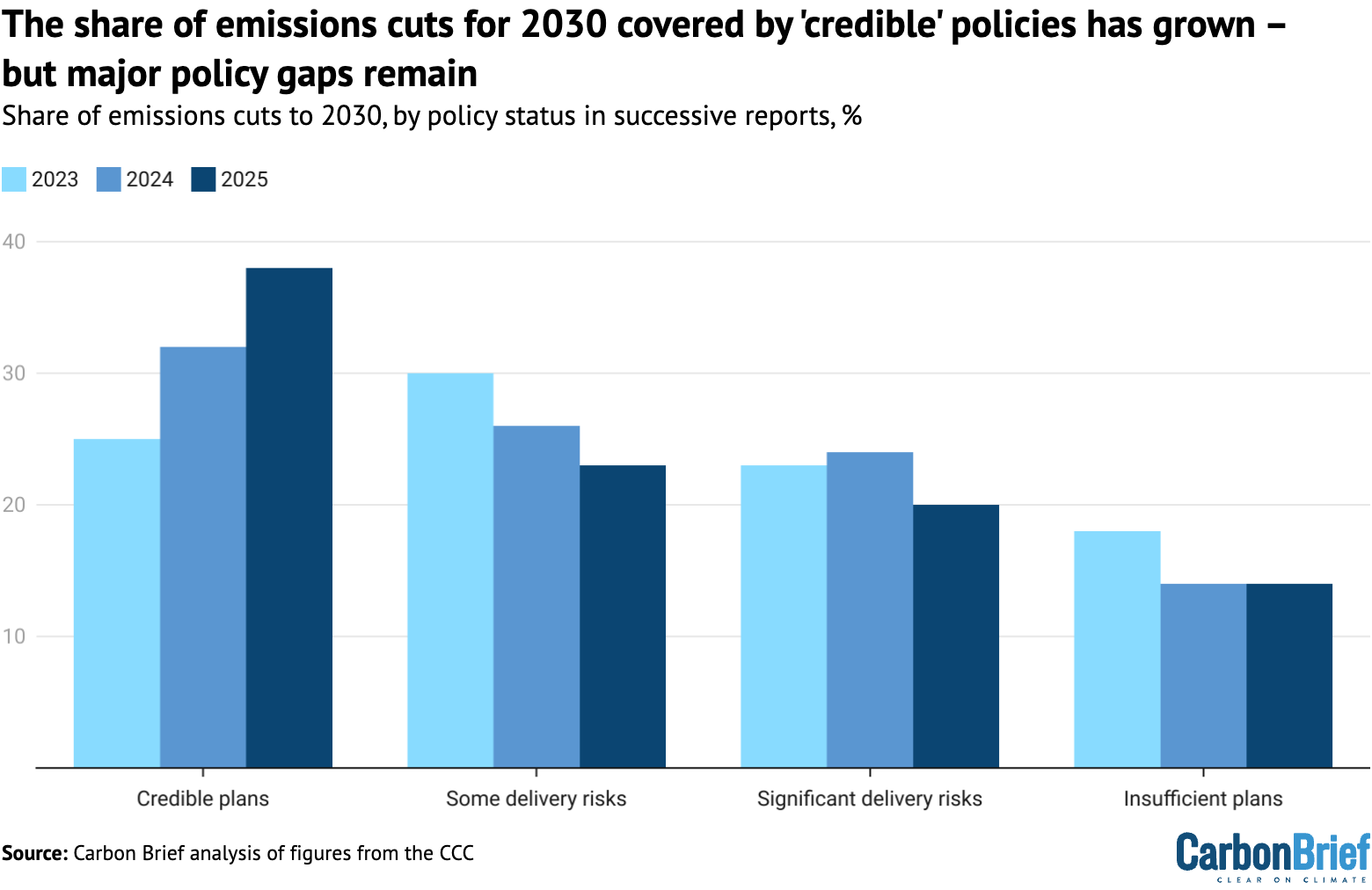

It says that 38% of the emissions cuts needed to hit the UK’s 2030 target are now backed by “credible” policies, up from 25% two years earlier.

However, it says “significant risks” remain – and its top recommendation is for government action to reduce electricity prices, which would support the electrification of heat, transport and industry.

Carbon Brief has covered the CCC’s annual progress reports in 2024, 2023, 2022, 2021 and 2020.

- Change of tone

- Overall progress

- Policy gaps

- Road transport

- Buildings

- Industry

- Fossil fuels and hydrogen

- Electricity

- Agriculture and land

- Aviation and shipping

- Other sectors

Change of tone

This is the first progress report from the CCC to assess climate policy and action under the new Labour government, which took office in July 2024.

Last year’s edition had said that “urgent action is needed” and that the UK was “not on track” for its 2030 international climate goal, namely, a 68% reduction in emissions relative to 1990 levels.

In contrast, the 2025 report says: “This target is within reach, provided the government stays the course.”

Speaking at a pre-launch press briefing, CCC interim chair Prof Piers Forster said: “[This is] an optimistic report, [showing] that it is possible for the country to meet its climate commitments.”

Moreover, in comments aligned with the shift in language since last year, he said that the report was “more optimistic” than the 2024 edition. Forster explained:

“We are not a political organisation and our job as a committee is just to look at the evidence, but, in terms of looking at the evidence, we are more optimistic than we were this time last year.”

The reasons for this were a mixture of policies from the previous government starting to deliver and the impact of decisions taken by the new administration, he said.

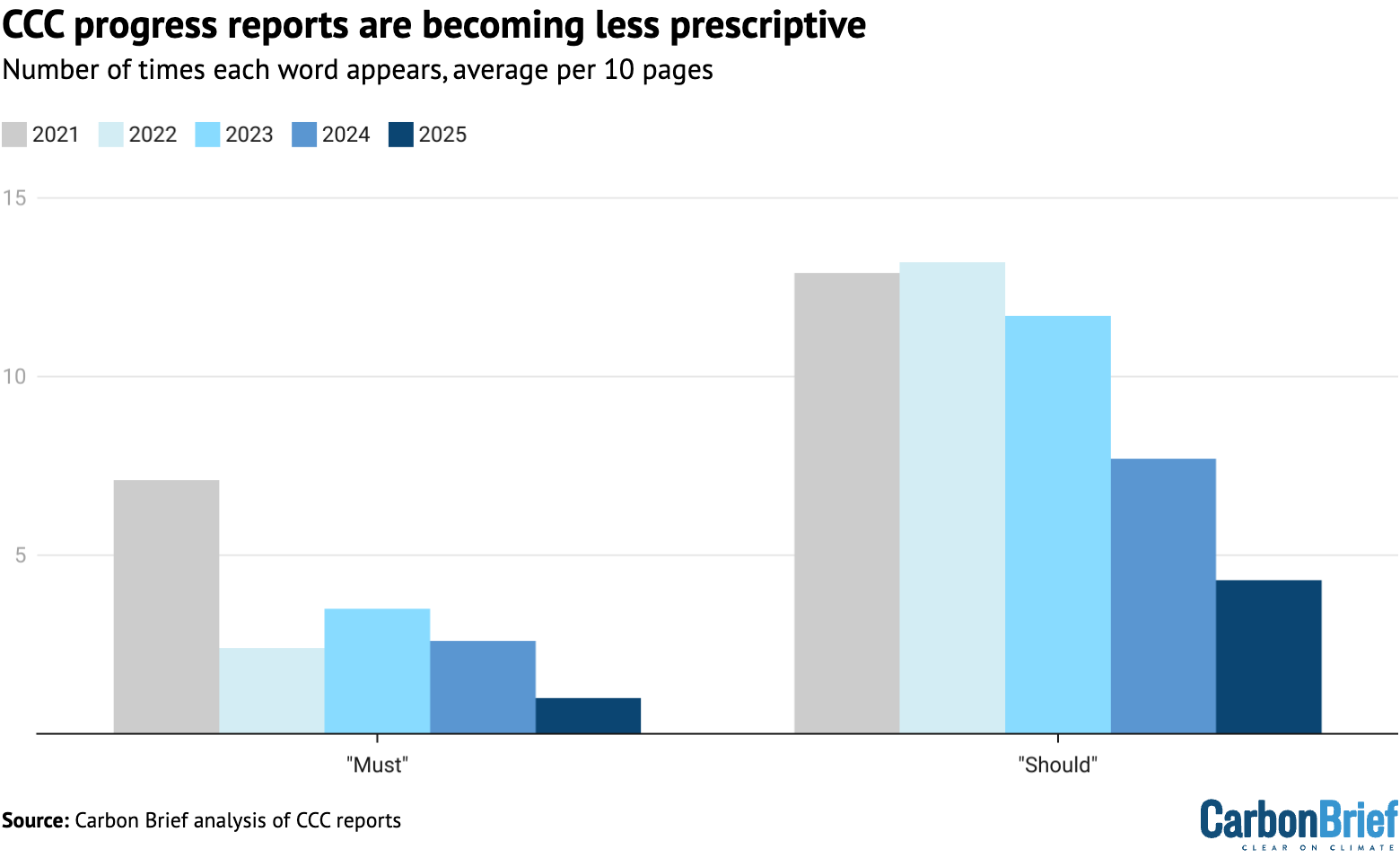

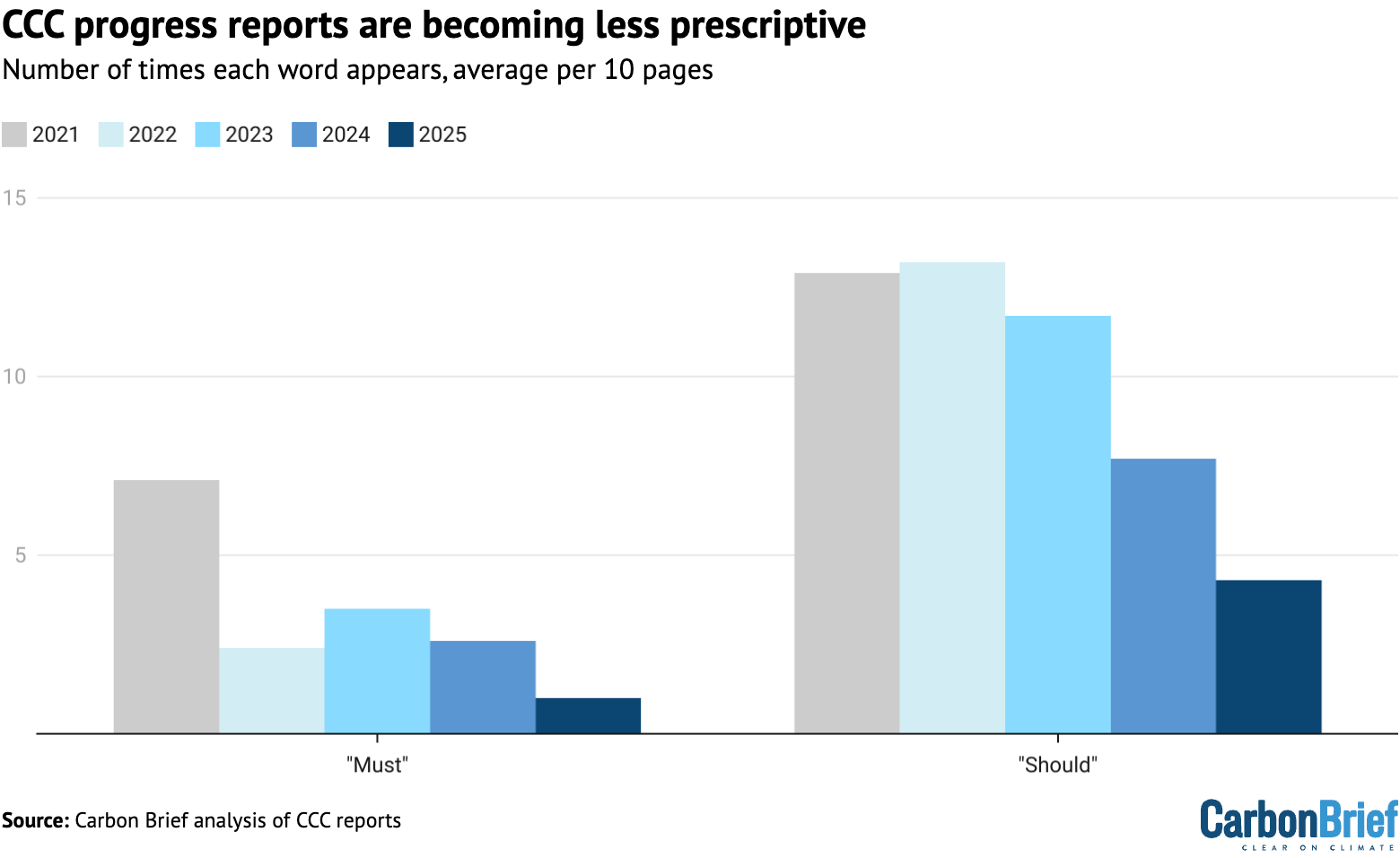

While the tone is relatively optimistic, the latest progress report uses less prescriptive language than previous editions, according to Carbon Brief analysis shown in the figure below.

For example, the word “must” occurs once every 10 pages in this year’s report, down from seven times in 2021. Similarly, the word “should” only occurs four times per 10 pages, down from 13.

This shift in language appears to be a continuation of the approach taken by the committee in its advice on the UK’s seventh “carbon budget”, published in February.

(Under the Climate Change Act 2008, the government has until June 2026 to legislate for this budget, which is a legally binding emissions limit for the five-year period from 2038 to 2042.)

The committee has faced inaccurate criticism from some opponents of climate action, who have argued that it was, in effect, setting government policy.

Pushing back on this, Forster had reiterated in February: “[O]ur core responsibility…is to give…the very best non-partisan advice possible…It’s not up to us to make the policy, it’s up to government.”

Beyond the overall tone of the latest progress report, it also puts a stronger emphasis than last year’s on the need for action to reduce emissions.

It sets out the rationale for the world reaching net-zero carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions to stop global warming, but also asserts the benefits this would bring to the UK in terms of energy security, a more efficient economy and lower bills:

“[C]ontinued reliance on fossil fuels undermines UK energy security…[A] fossil-fuelled future would leave the UK increasingly dependent on imports, and energy bills would remain subject to volatile fossil fuel prices.”

In language that could be interpreted as pushback against the leader of the opposition, the Conservative’s Kemi Badenoch, who recently falsely claimed that reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 was both “impossible” and only possible “by bankrupting us”, the CCC report states:

“The science is unambiguous. Only by achieving net-zero CO2 emissions, with deep reductions in other greenhouse gases, can the UK stop contributing to an ever-warmer climate…The 2050 net-zero target for the UK remains deliverable and affordable, with whole-economy costs estimated at an annual average of 0.2% of GDP.”

Asked directly if he agreed that the net-zero by 2050 target was “impossible” and would come with “catastrophic” costs – as Badenoch has asserted – Forster said that on the contrary, it was “possible” and would, “ultimately, be good for the UK economy”. He told journalists:

“We think that, provided there is further government policy, it is possible both to reach our [2030 target], our carbon budgets and then, ultimately, get to net-zero…[and that] while the benefit doesn’t come instantly…it will, ultimately, be good for the UK economy.”

The report also makes the point that the UK is far from alone in its efforts, with global investments in clean-energy technologies reaching $2tn last year, double the sum going to fossil fuels. It adds:

“Most of the world is investing heavily in low-carbon technologies, driven by falling costs, energy security concerns and a realisation of the need to respond to rising climate impacts.”

(This is despite the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement and a “period of uncertainty” in international relations since the US election, the report notes.)

Overall progress

Last year’s report, published just days after Labour’s “landslide” election victory, had set the scene for the new administration, saying that it needed to “make up lost ground” to get back on track.

That report had called on the new government to “limit the damage” from Conservative climate policy rollbacks, which had been implemented ahead of the election.

This year’s report looks at how things have progressed since then, based on three sets of metrics:

- First, it looks at changes to the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions over the past year.

- Second, it looks at indicators of progress on the ground, such as the uptake of electric vehicles (EVs), the rollout of electric heat pumps and the rate of tree-planting.

- Third, it looks at policy changes introduced over the past year by the new government.

The assessment includes policy changes introduced up until 23 May 2025, meaning that it does not consider the June spending review or the industrial strategy published earlier this week.

Greenhouse gas emissions have more than halved since 1990, with a 50.4% reduction, making the UK “one of the leading economies in the world”, Forster said. The report adds:

“The UK should…be proud of its place among a leading group of economies demonstrating consistent and sustained decarbonisation.”

It says that UK emissions fell again during 2024, with a 2.5% reduction marking the tenth year of steady decline, excluding the Covid-19 pandemic and subsequent rebound.

Echoing Carbon Brief analysis published in March, the CCC says that the latest drop in emissions was due to the power sector, industry and transport, where EVs are starting to have an impact.

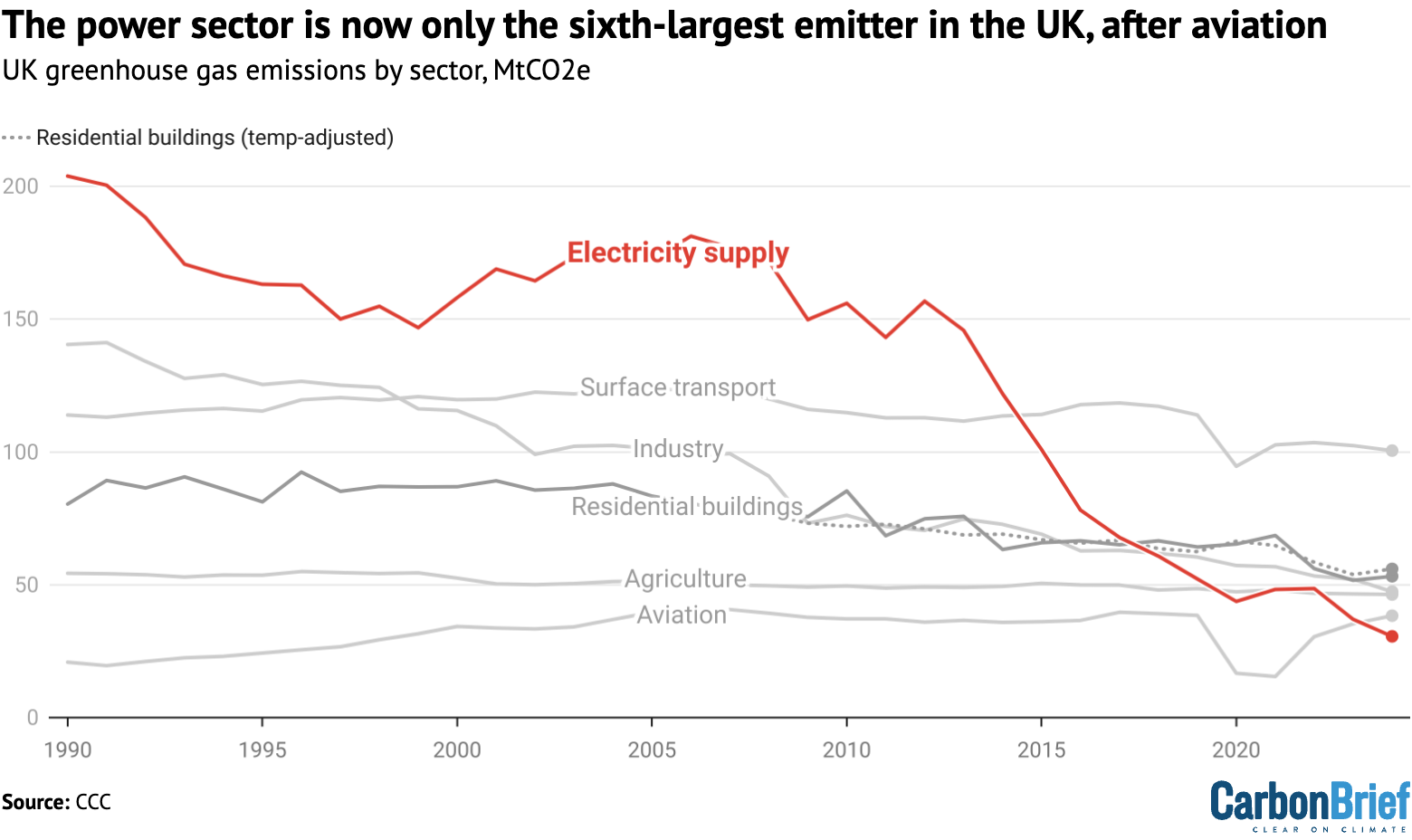

However, the report emphasises once again that progress to date has largely come in the electricity sector, where the UK became the first country in the G7 to phase out coal power in 2024.

Indeed, the CCC says that electricity supply is now only the UK’s sixth-largest source of emissions, after surface transport, buildings, industry, agriculture and aviation, as shown in the figure below.

In order to continue cutting emissions to meet UK climate goals, the CCC says that reductions will be needed across a broader range of sectors, including transport, buildings, industry and land-use.

The pace of emissions cuts outside the power sector – an average of 8m tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) per year since 2008 – is roughly on track for the fourth carbon budget covering 2023-27.

However, the report says this pace will need to “more than double” toward the end of the decade, hitting 19MtCO2e per year, in order to hit the UK’s NDC and sixth carbon budget.

Turning to the indicators of progress on the ground, the CCC says that there are some “clear signs” of such shifts starting to take place, in areas such as transport, buildings and land-use.

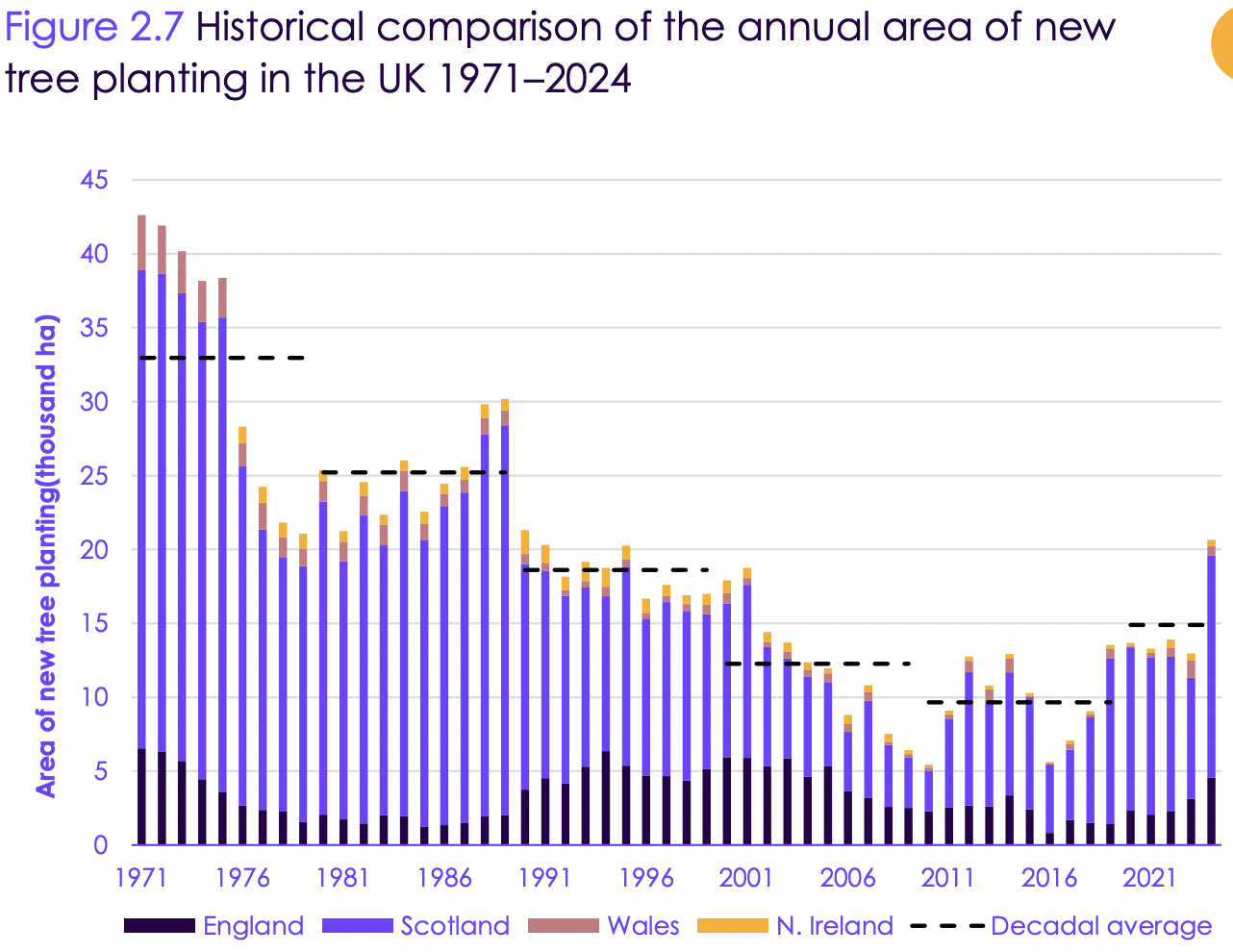

For example, the report points to “significant increases” in the rates of heat-pump rollout (up 56% year-on-year in 2024), tree-planting (+59%) and peatland restoration (+47%).

(See the sections below for further detail on policies and progress in each sector.)

Policy gaps

Turning to its assessment of government climate policy, the CCC report says there has also been some “positive progress” since Labour came to office last year.

Specifically, it points to the removal of planning barriers for onshore wind and heat pumps, as well as implementation of the “clean heat market mechanism” to drive heat-pump sales, reinstatement of the 2030 combustion car ban and publication of the 2030 clean-power action plan.

As a result, the CCC says that there are now “credible policies” in place to make 38% of the emissions cuts needed to hit the UK’s 2030 target, up from 25% in 2023 and 32% last year.

At the same time, the share of emissions savings subject to policies facing “some” or “significant risks” has fallen from 53% in 2023 and 50% in 2024, down to 43% in the latest report.

These improvements are illustrated in the figure below, which shows that the credibility of UK climate policies towards the 2030 target has been steadily increasing.

Nevertheless, there are still “insufficient plans” to make 14% of the cuts needed by 2030, the same share as last year. The biggest policy gaps are around heat-pump rollout, the report says.

The CCC says: “With 39% of policies and plans needed to hit the 2030 NDC rated as having significant risks, or insufficient or unquantified plans, the government must act swiftly.”

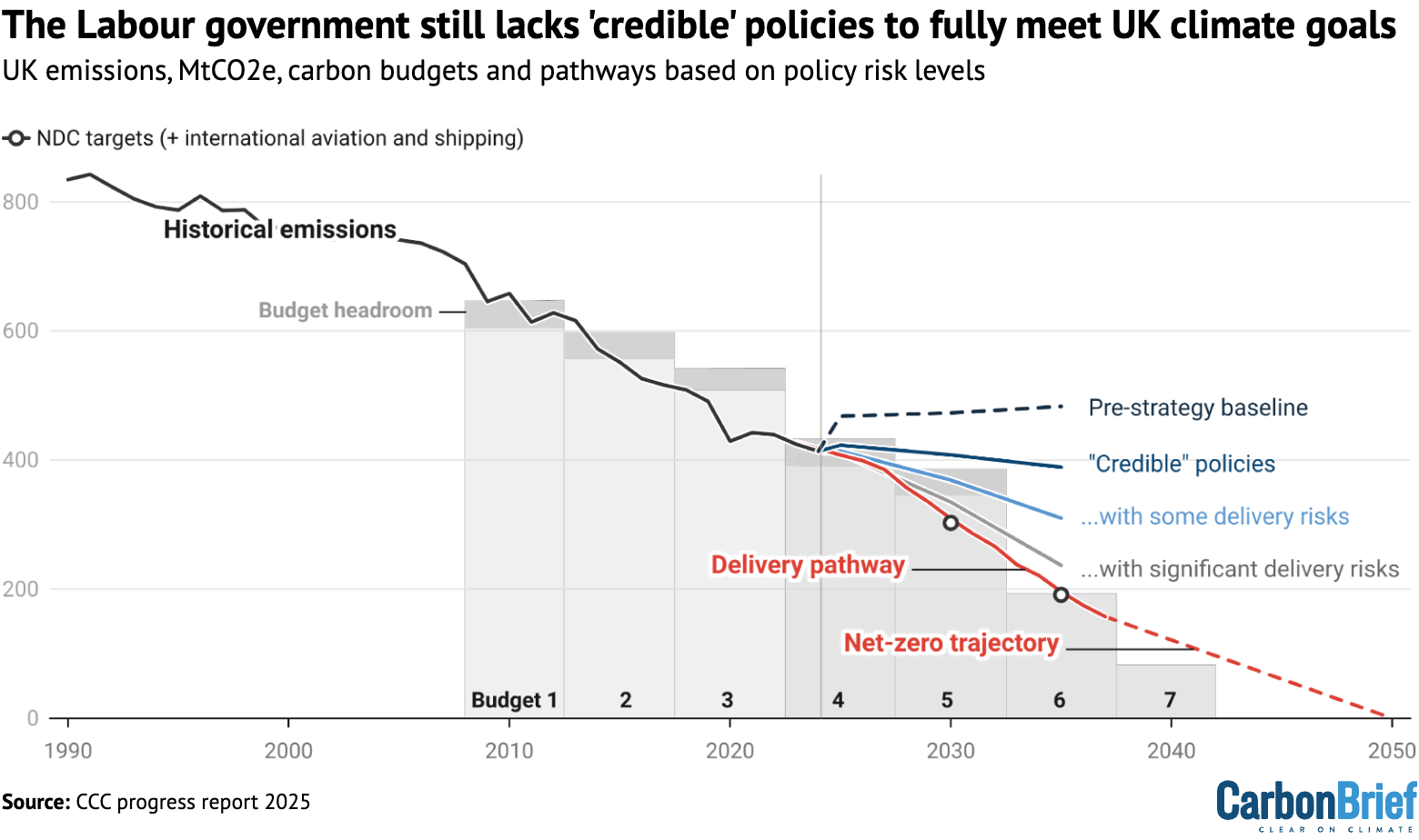

The figure below illustrates the implications of falling to “act swiftly” more clearly.

If only the most “credible” policies actually deliver emissions savings (solid dark blue line) then the UK would miss its international targets for 2030 and 2035 (black circles) by significant margins.

The UK would get somewhat closer to its goals, if emissions cuts are successfully achieved as a result of policies subject to “some” (light blue) or “significant” delivery risks (grey line).

At the pre-launch briefing, Dr Emily Nurse, head of net-zero at the CCC, told journalists that further action was needed to get on track for the 2030 target. She said:

“Around three-fifths of what’s needed is covered by either credible plans or [those] having some risks…The UK can hit its upcoming emissions reduction targets and remain on track for net-zero, but only with further policy action.”

The government has the chance to fill these policy gaps when it publishes its updated “carbon budget delivery plan”, which has a deadline of 29 October this year.

This plan must set out how the government intends to meet the UK’s legally binding climate goals, after the previous administration’s plan was ruled unlawful by the High Court.

While there has been “good or moderate progress” on 20 of the 35 policy recommendations made last year, the CCC says there has been “no progress” on its top recommendation to make electricity cheaper.

The report says this remains its top recommendation for the second year in a row.

The reason for emphasising this, it says, is that electrification of transport, heat and industry will be the key to making required emissions cuts over the next decade, according to the CCC, with these shifts being facilitated by the expansion and continued decarbonisation of the power sector.

CCC chief executive Emma Pinchbeck told journalists that making progress in lowering electricity prices was “absolutely critical”, particularly relative to the price of gas. She said:

“The reason we keep banging on about [this], very simply, [is] that the evidence from every other country that’s had a successful rollout of electric technologies – particularly for heat – is that you need a three-to-one electricity-to-gas price ratio.”

(At present, domestic electricity prices are roughly four times higher than gas prices.)

Pinchbeck reiterated the committee’s call for the government to remove policy “levies” from electricity bills, adding that failing to do so would mean “slowing down” the transition. She said:

“If you’re effectively taxing your future fuel, you’re slowing down your energy transition, when the economy is going to become more and more dependent on electricity…It is just sensible economic policy to have cheap fuel going into your economy.”

While Pinchbeck welcomed plans in the government’s just-published industrial strategy to cut levies on industrial electricity bills, she said that it should do the same for households.

Road transport

Road-transport emissions fell for a second consecutive year in 2024, says the report.

The number of electric vehicles (EVs) on UK roads is roughly doubling every two years.

If this trend continues, the road-transport sector will produce the emissions savings required for its contribution to the UK’s 2030 climate target, the CCC says (see below).

EVs made up 19.6% of new car sales in 2024, compared to 16.1% the previous year, according to the report. In the first quarter of 2025, this figure rose to 20.7%.

This represents “strong growth”, but is below the headline targets of the zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) mandate, a government regulation that requires car manufacturers to sell an increasing percentage of zero-emission vehicles each year, the CCC says.

The mandate targets a 22% market share for 2024 and a 28% share for 2025, according to the CCC.

The CCC notes that lower-cost EVs are becoming increasingly available. It adds that “price parity with petrol cars has already been reached in parts of the second-hand market”, with this milestone set to arrive for new cars by between 2026 and 2028.

Overall, there has been a “small improvement” in the UK’s policy efforts to decarbonise road transport since last year’s report, it says.

This is largely down to Labour’s decision to reinstate a 2030 ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel vehicles, which was weakened to 2035 under Conservative prime minister Rishi Sunak, explains the report.

The CCC describes the move as a “welcome market signal to accelerate the transition to EVs”.

As well as reinstating the 2030 ban, the government announced changes to the ZEV mandate.

The government essentially weakened the mandate by extending flexibilities and allowing the sale of hybrid vehicles between 2030 and 2035.

Ministers said this move was in response to import tariffs announced by Donald Trump.

The CCC says the changes “risk allowing existing planned plugin hybrid vehicle sales to slightly reduce the emissions savings from EVs”, adding:

“It is also possible that manufacturers could divert investment towards [hybrids], diluting the consumer offer for EVs – we currently think that this risk is minimal due to progress in scaling up the EV market to date, but it is something that we will monitor closely.”

It adds that “for the transition to accelerate, further reductions in the cost of purchasing EVs, as well as improved access to, and reduced costs of, local public charging, are needed”.

Buildings

Heat pump installations increased by 56% in 2024 compared to the year before, the report says. Some 98,000 heat pumps were installed.

A total of 23,000 heat pumps were installed under the Boiler Upgrade Scheme, which allows homeowners to claim grants for replacing fossil-fuel boilers. This is an increase of 83% on 2023 levels, says the CCC.

However, the speed at which heat pumps are rolled out remains one of the “biggest risks” to the UK meeting its 2030 climate target, it adds.

The UK’s heat pump market share is around 4%, much lower than comparable countries, such as Ireland (30%) and the Netherlands (31%), the CCC says.

The government has taken steps to “remove planning barriers” for heat pumps. This includes amending the planning policy in England to remove the requirement for planning permission for heat pumps located less than 1m from a property boundary.

However, the government has “not yet provided clarity on whether [it] will continue with the proposed phase-out of new fossil fuel boiler installations from 2035”, or “make alternative plans to ensure that low-carbon heating reaches the installation rates required”, the CCC says.

The report adds that the ratio of residential electricity to gas prices is “significantly off track”.

The ratio is important because it underpins the “underlying cost savings of switching to electric technologies are reflected in the bills paid by households and businesses”, the CCC says, continuing:

“Action has not been taken to remove policy costs from electricity prices which would address this, despite it being our first recommendation last year…Currently, a typical household with a heat pump is paying around £490 per year in policy costs, which inflate their bills above the underlying cost of the additional electricity used.”

Data from other nations suggests that the “market share of heat pump installations are correlated with more favourable electricity-to-gas price ratios”, says the CCC (see chart below).

Forster told the press briefing that the CCC’s “biggest recommendation” to government remains reducing the price of electricity in relation to gas:

“By far the most important recommendation we have for the government is to reduce the cost of electricity, both for households and for businesses and industry as well…If we want the country to benefit from the transition to electrification, we have to see it reflected in utility bills.”

The report adds that, on efforts to increase the energy efficiency of residential buildings, the “proportion of homes with insulated cavity walls has steadily increased over recent years, but this will need to accelerate later in the decade” to be in line with net-zero.

Industry

Industry emissions decreased by 4.7MtCO2e in 2024, compared to the year before, the CCC says. Emissions are now 48% lower than 2008 levels.

From 2023-24, annual emissions dropped quickly due to the removal of blast furnaces at Port Talbot steelworks in 2024. They are due to be replaced by electric arc furnaces by 2027, with the move leading to 2,500 job losses.

The government should have developed a “more proactive and decisive transition plan” for Port Talbot and the report describes the UK’s upcoming steel strategy as “an opportunity to set out plans for the low-carbon transition at Scunthorpe steelworks and other UK steel production”.

To deliver the emissions savings needed to meet the UK’s 2030 climate goal, companies will “increasingly need to switch to electric alternatives to fossil-fuelled technology”, the report says, adding:

“A high ratio of [industrial] electricity-to-gas prices currently presents a barrier to this.”

It adds that, currently, “there is now no major source of government support for manufacturers to invest in electrification”.

The CCC notes that the government did not launch the latest round of the Industrial Energy Transformation Fund, which was due in December 2024. It has “not clarified whether this or similar funding will continue”.

On 23 June, the UK government announced a 10-year industrial strategy, including measures to slash the price of electricity for energy-intensive businesses from 2027 by exempting them from green levies.

In the press briefing, Pinchbeck described the move as “good”, but urged the government to introduce similar measures for household electricity bills, too. (See: Buildings.)

On efforts to introduce carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies to UK industries, the report says progress “is not on track to be deployed at the pace required” by government plans to reach net-zero.

Fossil fuels and hydrogen

The report says that the UK’s “continued reliance on fossil fuels undermines energy security”, continuing:

“Household energy bills rose sharply following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and have remained high since. It is the price of gas that has driven up both gas and electricity bills.”

(See Carbon Brief’s factcheck on what is causing high electricity bills in the UK.)

The report does not directly address the Labour government’s policies on oil and gas production in the North Sea.

Labour has ruled out new oil and gas licences. However, the government has indicated it might approve new projects that already have a licence, if they can pass a new environmental impact assessment that will consider the emissions from burning the oil and gas produced.

In regards to the North Sea, the report says:

“With North Sea resources largely used up, a fossil-fuelled future would leave the UK increasingly dependent on imports and energy bills would remain subject to volatile fossil fuel prices.”

The CCC adds that the “main progress in the fuel-supply sector in the past year has been around low-carbon hydrogen production”.

In the 2024 autumn budget, the government confirmed support for 11 “electrolytic”

hydrogen production projects, which are expected to start operating by the end of 2026. (These projects use electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen.)

Electricity

The UK’s transition away from fossil fuels to renewable energy in its electricity supply continued to drive the bulk of emissions reductions in 2024, the CCC says. It accounted for 41% of the total in-year reduction in emissions.

From the 1990s until 2024, the power sector has transformed from the largest source of emissions to only the sixth largest, behind aviation. (See: Overall progress.)

The UK’s last coal-fired power plant, Ratcliffe-on-Soar, closed in October 2024. (See Carbon Brief’s detailed explainer on how the UK became the first G7 nation to phase out coal.)

Coal emissions from electricity generation were 99% lower in 2024 than in 2008 and will reach zero in 2025, the CCC says. It describes this as a “major milestone on the UK’s path to a decarbonised power system”.

Falling gas generation accounted for 72% of emissions reductions in the power sector in 2024, the CCC says.

The electricity supplied by gas fell by 15% in 2024, compared to the previous year. This was “made up with roughly equal proportions of imports and low-carbon generation”.

The rollout of wind and solar capacity in 2024 was larger than in any of the previous six years, the report says.

But to achieve the government’s goal of “clean power” by 2030, total renewable capacity will need to more than double.

Based on projects in the pipeline, both offshore and onshore wind “appear on track” for the government’s goal, according to the CCC.

However, “roll-out of solar is significantly off track and will need to improve to deliver its contribution to a decarbonised electricity system”.

The report says that, overall, “positive policy progress has been made in decarbonising electricity supply over the past year”.

It continues that “concrete steps have been made to remove barriers and support the deployment of low-carbon technology”.

These steps include removing barriers facing onshore wind developments, “streamlin[ing]” the approval of nationally significant infrastructure, including renewable projects and introducing reforms to speed up connecting projects to the grid.

However, the CCC adds that there are “remaining uncertainties on the future electricity market arrangements and further challenges to deploying infrastructure to overcome”.

Agriculture and land

There was a “significant increase” in both tree-planting and peatland restoration in 2024, the report says.

Some 20,700 hectares of new trees were planted, an increase of 59% on the year before and the highest rate in 20 years, it adds, as shown in the chart below.

Over the same period, the restoration of peatlands increased by 47%.

This “demonstrates that a rapid increase in rates is feasible” for the land-use sector, the CCC says.

However, woodland creation remains “slightly off track”. (Carbon Brief reported last year that successive UK governments have fallen so far short of their tree-planting targets since 2020 that they have failed to plant an area of forest nearly equivalent to the size of Birmingham.)

In addition, Scotland accounted for 73% of the total trees planted from 2023-24 and the CCC has “concerns that recent reductions in funding for woodland creation in Scotland could reverse this trend”.

A target to have 35,000 hectares of peat under restoration in England by 2025 is also “expected to be missed”.

Livestock numbers continued to fall in 2024, the report says.

Meat eating has declined steeply over the past couple of years. The average amount of meat eaten per person each week dropped by around 100g from 2020-22, according to CCC data.

Pinchbeck told the press briefing that meat-eating in the UK is now lower than what the CCC had anticipated in its central pathway for meeting net-zero:

“There’s lots of factors behind that, including the cost of living crisis. So we are not necessarily saying that trend will increase. Farming is facing a number of pressures, outside having to deal with a changing climate, reduced crop yields [and] difficulty making farms sustainable.”

Both the reduction in livestock and meat eating are “key to freeing up land required to increase tree-planting and peatland restoration”, the report says.

The government’s progress on addressing land-use sector emissions with policies has been “mixed” over the past year, according to the CCC.

The government is expected to produce a long-awaited land-use framework by the end of this year, but it “remains unclear how this framework will drive change on the ground”, the advisers say.

The government paused the sustainable farming incentive, part of the environmental land management (ELM) schemes, in March 2025.

This was due to all of the funding being allocated, which is “positive”, says the CCC. However, the decision has left a “gap in delivery grants for on-farm actions”.

The Nature for Climate Fund has been extended by one year, but is “unclear” what will happen to this scheme in the long term, it adds.

Aviation and shipping

Emissions in the aviation sector increased by 9% year-on-year in 2024, “marking a return to pre-pandemic levels”, the report says.

In government and CCC scenarios for net-zero, emissions stay flat and start slowly decreasing over the rest of the decade, the report says, adding:

“Aviation emissions will likely exceed the trajectories assumed in all [these] pathways if they continue to increase, posing a risk to the UK’s emissions targets.”

The biggest driver of aviation emissions since 1990 has been “rising demand for international flights, particularly leisure”, it continues.

Aviation now causes more emissions than the UK’s entire power grid. In 1990, aviation emissions were 10 times lower than those from electricity, according to the report.

The CCC “recommends that the government should develop and implement policy that ensures the aviation sector takes responsibility for mitigating its emissions and, ultimately, achieving net-zero”, adding:

“This includes paying for permanent engineered removals to balance out all remaining emissions. Robust contingencies should also be in place to address any delays in decarbonisation, including through managing the forecasted increase in aviation demand.”

The share of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) as a proportion of all jet fuel rose from 0.7% to 2.1% from 2023-24, the CCC says.

It notes that the SAF mandate came into force in January 2025 and the sustainable aviation fuel bill was introduced to parliament in May.

Achieving the government’s target of 10% of jet fuel from SAF by 2030 “remains uncertain as different types of SAF will need to scale up”, it adds.

There are currently no operational UK SAF plants, but some are under construction.

On shipping, the report notes that the UK has set out a maritime decarbonisation strategy, with an aim to reduce the domestic maritime sector’s fuel lifecycle emissions to zero by 2050 and interim goals of cutting pollution by 30% by 2030 and 80% by 2040, compared to 2008.

The targets are “broadly aligned” with government plans for net-zero, the CCC says.

Other sectors

Another sector tracked by the CCC is “engineered removals”, technologies that suck CO2 out of the atmosphere.

Aside from small experiments, there is no deployment of such technologies in the UK. However, the government’s pathway for net-zero expects such methods to remove 6MtCO2e from the atmosphere by 2030, the report says, adding:

“This sector will need to develop and scale up notably over the coming five years.”

One of the CCC’s “top 10” priority actions is for the government to “finalise business models for large-scale deployment of engineered removals”.

On this, the advisers say:

“There has been little progress…This puts the contribution of engineered removals to the UK’s 2030 NDC at increasing risk.”

Another issue assessed by the CCC is waste, which produced 26.7MtCO2e in 2024, making it the eighth most polluting sector.

The report says there has been “some progress” on waste policy, but notes the government is “yet to confirm its intention to prevent biodegradable waste from going to landfill, a key measure to reduce emissions from waste”.

The post CCC: UK climate advisers now ‘more optimistic’ net-zero goals can be met appeared first on Carbon Brief.