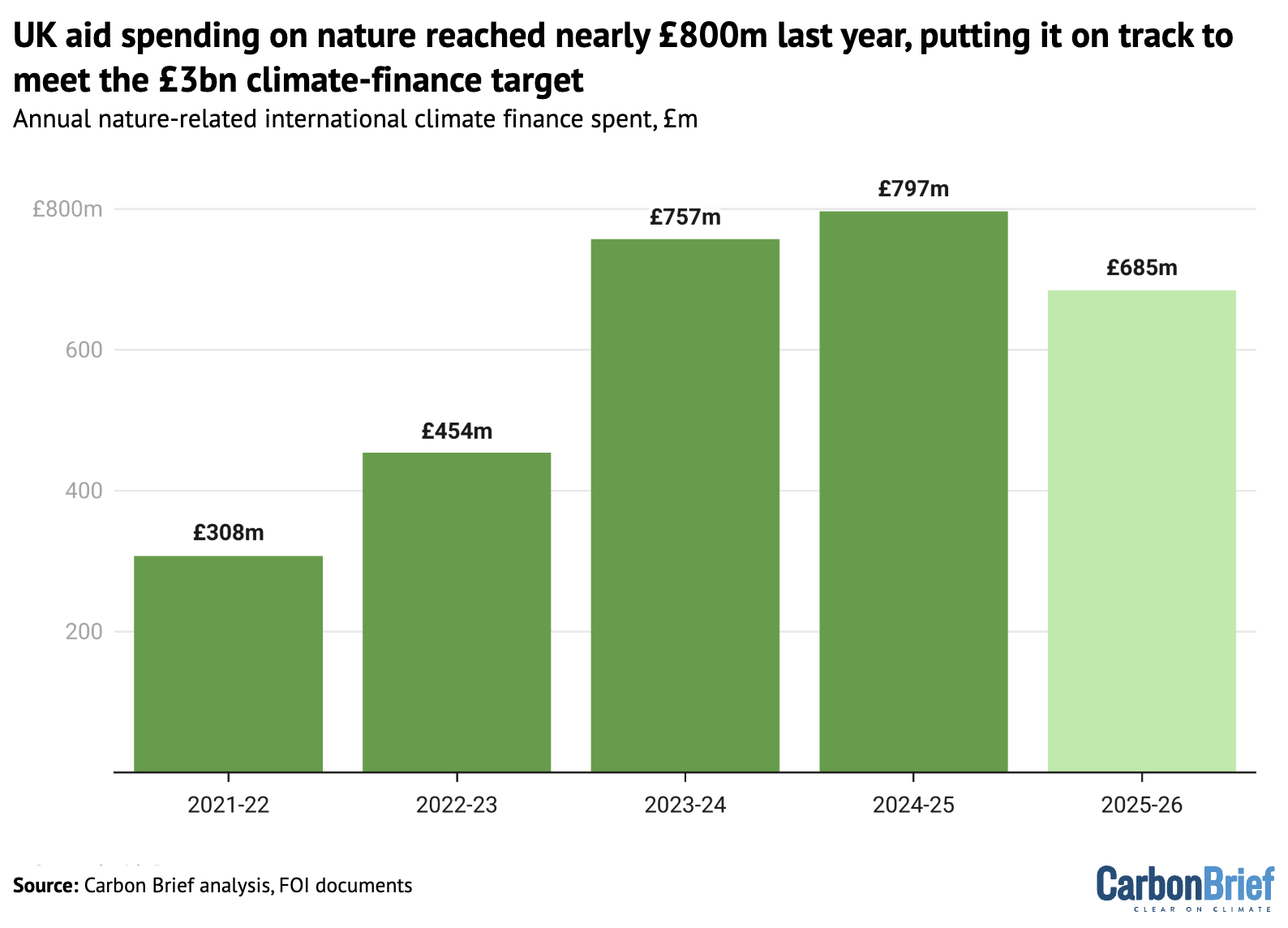

The UK’s climate-aid spending on “nature protection and restoration” reached record levels of nearly £800m last year, according to government figures obtained by Carbon Brief.

The data suggests the UK is on track to achieve its five-year pledge to provide £3bn in nature-related funds for developing countries by 2026.

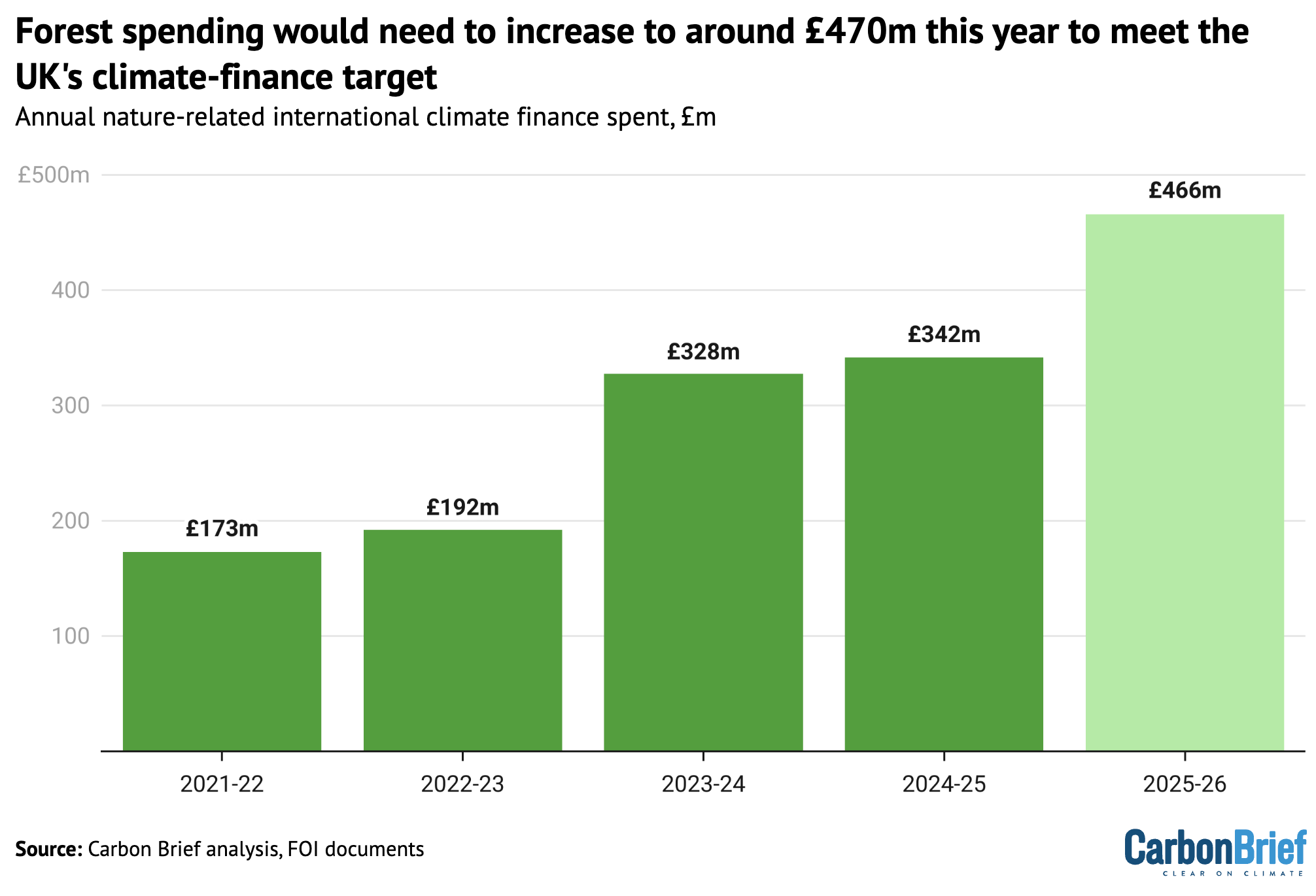

Funding for forest protection has also increased, but will need to rise by an additional £100m this year in order to meet the target of £1.5bn, within the £3bn total.

The latest figures, provided to Carbon Brief via freedom-of-information (FOI) requests, include climate-aid contributions to forest-dense regions, from the Amazon to the Congo Basin.

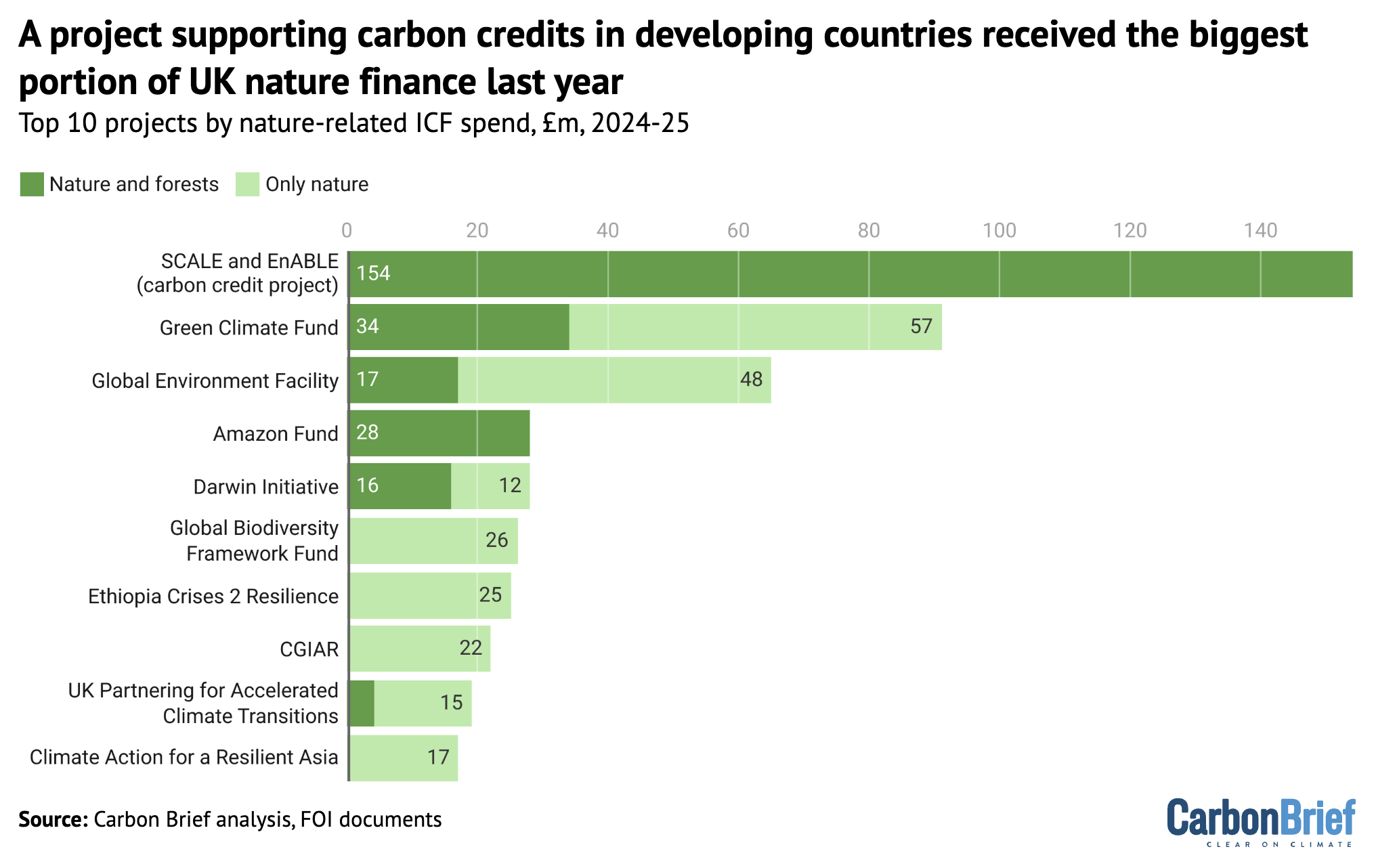

By far the largest slice of last year’s finance – amounting to almost half of forest funds – came from a £153.9m project supporting controversial carbon-offsetting schemes in developing countries.

This is one of the largest donations the UK has made to a nature-and-forests project since 2021, outstripping others that have been underway for years.

Targets on track

The UK has a target to provide £11.6bn in climate finance over a five-year period ending in 2026. This is the nation’s contribution to a wider effort under the Paris Agreement to provide developing countries with funds that help them deal with climate change.

Within this target, the previous government had pledged in 2021 that £3bn would go to projects that “protect and restore nature”. This, in turn, was to include £1.5bn for forest-related projects.

Last year, the Labour government confirmed that it would “continue to honour” these sub-goals, along with the overall £11.6bn target it inherited.

Alongside many other developed countries, however, the UK has announced major cuts to its aid budget in recent years, placing climate-focused spending under pressure.

Nevertheless, Carbon Brief analysis suggests that the country is on track to meet its £11.6bn climate-finance target. This is partly due to accounting changes that have allowed the government to include additional forms of finance in its figures, without committing as much new money.

Government data obtained by Carbon Brief via FOI suggests that the UK is broadly on track to meet its nature-and-forest targets as well.

UK spending on nature-related programmes reached £796.6m in 2024-25, bringing the cumulative total to £2.3bn. This means it would need to spend £684.8m on such projects in 2025-26 to hit the target, as shown in the chart below.

Projects covered by the “nature” target include an initiative tackling water insecurity and pollution in Nepal, support for “climate-smart agriculture” in African countries and a fund aimed at delivering the global target to protect “30% of earth’s land and sea for nature”.

For the forest-finance target, which only covers projects addressing deforestation or forest restoration, spending on relevant projects reached £341.6m in 2024-25. This brings the cumulative figure up to just over £1bn since 2021.

Forest aid would, therefore, need to increase by more than £100m to £466m in 2025-26, in order to meet the £1.5bn goal, as shown in the chart below.

While this is a fairly steep increase, the government’s climate-finance targets were always designed to be backloaded, with more spending planned towards the end of the five-year period.

UK aid spending is set to drop sharply again in 2026-27, beyond the timeframe of current climate-finance goals.

The government has said it will continue to prioritise climate projects, but unpublished analysis of government forecasts by the Center for Global Development (CGD) – shared with Carbon Brief – suggests the departments financing these areas face major cuts.

The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) and Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), provided nearly half of all nature finance in 2024-25. They will see their aid spending drop by 59% and 45%, respectively, in 2026-27, which is a steeper drop than the aid budget as a whole, according to the CGD estimates.

Besides setting climate-finance targets, the UK also has obligations to provide biodiversity finance under the UN’s Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

In its FOI responses, the government stated that it has not recorded project-level biodiversity-focused spending over the five-year period covered by its climate-finance targets.

However, the government cites the £3bn nature target in its national biodiversity strategy and action plan (NBSAP) as one of the ways the UK is “clos[ing] the global biodiversity finance gap”. This indicates that the money is counted as both climate and biodiversity finance.

Carbon-offsetting

The largest portion of UK nature and forest spending last year was £153.9m from DESNZ for a project called “Scaling Climate Action by Lowering Emissions (SCALE)”.

This World Bank-backed programme funds projects that generate “high-integrity carbon credits” and provides technical assistance to help developing countries trade them.

The carbon credits will be generated via projects that curb carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by preserving or restoring forests and other ecosystems. These credits could then be purchased by companies or state actors, which may allow them to comply with climate targets while still producing emissions.

Combined with a smaller associated programme called “EnABLE” – which is designed to ensure that local communities receive benefits from carbon trading – the SCALE initiative made up a fifth of the total nature finance and 45% of forest funding in 2024-25.

(The government acknowledges in its FOI response that, despite counting 100% of the SCALE funding as forest-related, it “may benefit various ecosystems, not just forests”.)

The chart below shows the nature-and-forest projects that received the most funding from the UK in 2024-25, with combined spending on SCALE and EnABLE in the top spot.

Another initiative involving forest-related carbon credits – the Brazilian Amazon Fund – was also one of the top recipients of UK support last year, with £28.5m.

Carbon-offsetting is viewed by many as an important way to encourage external investment in nature protection, particularly for densely forested global-south nations.

Nevertheless, carbon credits, particularly those based on forest conservation, have been dogged by controversies. These range from Indigenous people being driven off their land to companies exaggerating the extent of forest protection and emissions savings.

Sarah Colenbrander, director of the climate and sustainability programme at ODI, tells Carbon Brief that the “risks to nature-based carbon offsets are well-documented”. She adds:

“Carbon and biodiversity markets have a role to play in tackling climate change and nature loss – but it is not obvious that the UK should allocate such large grants to this topic when there are many more proven, cost-effective options to cut emissions and protect the environment.”

The single payment of £153.9m means SCALE and EnABLE have received more money from the UK government than virtually any other nature projects since 2021.

The only larger overall recipients have been multilateral funds such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and the Global Environment Facility (GEF), which tend to be viewed favourably by developing countries.

These funds, which provide grants to developing country applicants, received large contributions from the UK last year of £90.8m and £64.8m, respectively.

When asked about the funding given to SCALE and EnABLE, a government spokesperson stresses the importance of tackling “the existential climate crisis”, adding:

“This includes putting Britain back in the business of climate leadership by supporting the reform of the global financial system and mobilising private finance for nature and to help developing countries accelerate the energy transition.

“This comes on top of working alongside other countries and the EU in the forests and climate leaders’ partnership to drive progress towards halting and reversing forest loss.”

Of the other top projects funded by the UK, some have a clear focus on nature, such as the Darwin Initiative. This project, which received £27.8m in 2024-25, is the “UK’s flagship international challenge fund for biodiversity conservation and poverty reduction”.

For others, nature is not the primary goal. Ethiopia Crises 2 Resilience, which received £24.9m last year, focuses on providing humanitarian relief from war and drought, but its annual review mentions “land treated through area enclosures, rangeland management, soil and water conservation, forage and forestry activities”.

Methodology

The nature-and-forest climate finance figures were provided to Carbon Brief via FOI by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO); the Defra and DESNZ.

The path to the £1.5bn and £3bn targets appears more achievable than it did in Carbon Brief’s previous analysis of nature-and-forests data, as the final 2023-24 figures provided by the government are higher than those obtained last year.

Unlike the other departments, FCDO declined to provide its 2023-24 figures last year, so Carbon Brief estimated the figures based on a dataset containing “provisional” figures for all climate-finance projects that year. However, this resulted in an underestimate, due primarily to larger-than-expected contributions to multilateral funds and banks being counted as nature-related.

Unlike the previous analysis, most of the figures provided via this year’s FOIs are the government’s “final” figures, meaning they are unlikely to change. For 2024-25, only Defra – which was responsible for 17% of nature finance that year – provided “provisional” figures.

The post Analysis: UK foreign aid for nature hits £800m record due to cash for carbon credits appeared first on Carbon Brief.