Cities around the world are facing more frequent and intense bouts of extreme heat, leading to an increasing focus on the use of air conditioning to keep urban areas cool.

With the UK having experienced its hottest summer on record in 2025, for example, there was a wave of media attention on air conditioning use.

Yet less than 5% of UK homes have air conditioning and those most vulnerable – older adults, low-income households or people with pre-existing health conditions – often cannot afford to install or operate it.

While air conditioning may be appropriate in certain contexts, such as hospitals, community spaces or care homes, it is not the only solution.

Our research as part of the IMAGINE Adaptation project shows that a universal focus on technical solutions risks deepening inequality and has the potential to overlook social, economic and environmental realities.

Instead, to adapt to record temperatures, our research suggests a keener focus on community and equity is needed.

Contextualising urban heat vulnerability

In the UK, heatwaves are becoming more frequent and severe. Moreover, the evidence points to significant disparities in exposure and vulnerability. By 2080, average summer temperatures could rise by up to 6.7C, according to the Met Office.

During the summer of 2023, around 2,295 heat-related deaths occurred across the UK, with 240 in the South West region. Older adults, particularly those over 65, were the most affected, government figures show.

A recent UN Environment Programme report highlights that there is an “urgent” need for adaptation strategies to deal with rising summer heat.

However, our research shows that framing air conditioning as the default solution risks worsening urban heat by increasing emissions and energy bills, as well as missing the opportunity to design more inclusive, human-centred responses to rising temperatures.

Addressing both gradual and extreme heat involves understanding who is most affected, how people move through cities and the role of social networks.

In recognition of this, cities around the world are already developing potential cooling strategies that combine low-emission interventions with community-based care.

Expanding the concept of ‘cool spaces’

In the UK, Bristol City Council is working on a “cool space” initiative with support from the European Research Council-funded project IMAGINE Adaptation.

The initiative aims to identify a network of public spaces that can offer respite during periods of extreme heat. These spaces can potentially include parks, libraries, community centres or even urban farms.

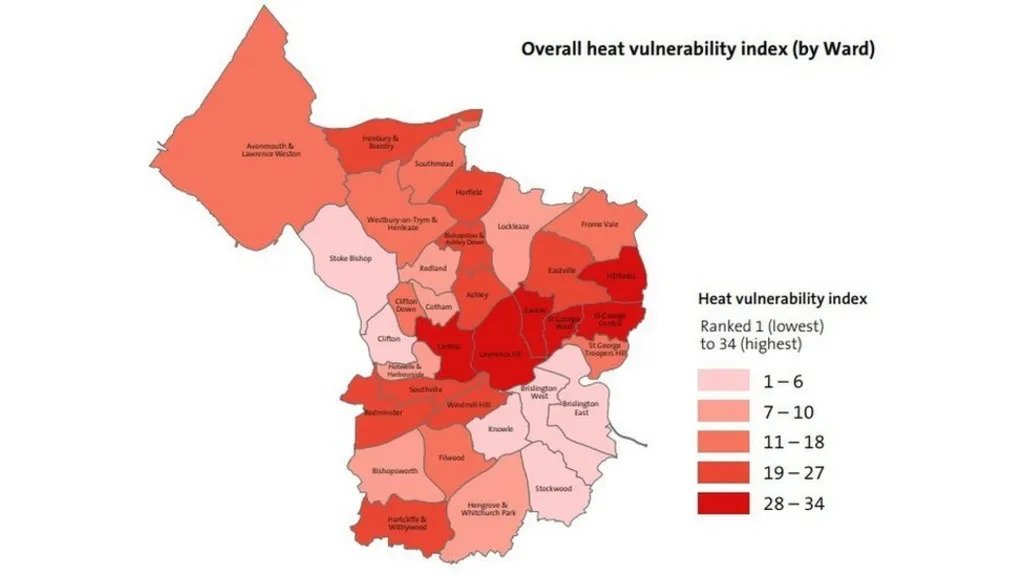

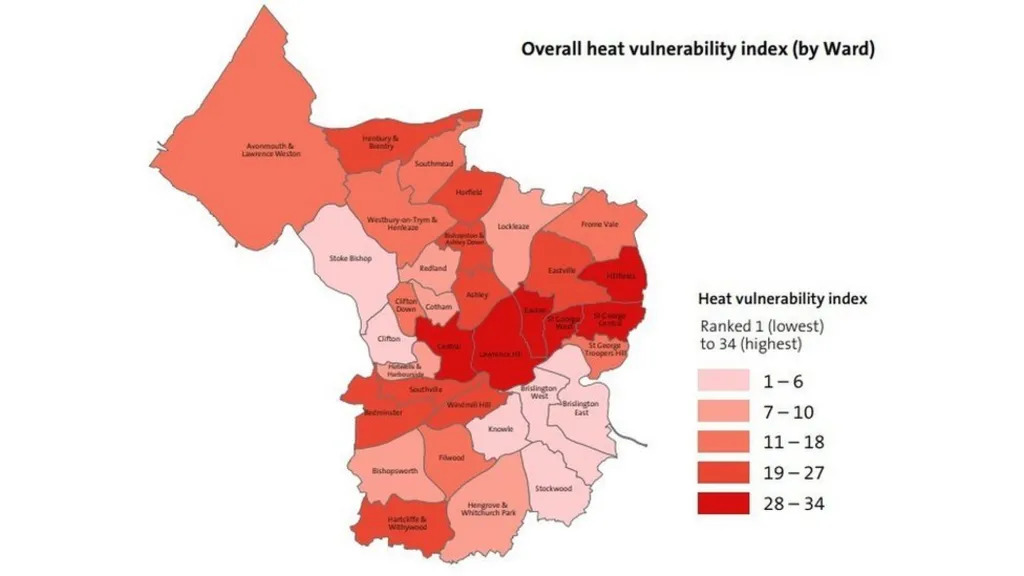

The map below shows how heat vulnerability varies across the city of Bristol, identifying neighbourhoods most at risk from current and future heatwaves.

But what makes a space “cool”? We used surveys, interviews and workshops to collectively come to an understanding of what a cool space means for Bristol communities.

What emerged from our work is that “cool” is about far more than temperature.

Shade, natural ventilation, seating, access to water and toilets all contribute to comfort, but they do not capture the full picture.

Social and cultural factors, such as whether people feel welcome, whether spaces are free to use or whether children can safely reach them, are equally important. For example, we found that while many community spaces are open to the public, people are often unsure whether they can spend time there without having to buy something.

Our research shows that the presence of a café, even unintentionally, can signal that time and space come at a cost. Clear signage, free entry, drinking water and toilets can help people feel that they are welcome to stay.

Additionally, our research highlights that it is important to recognise that public space is not experienced equally by everyone. Some city centre parks, for instance, may be seen as unwelcoming by people who do not drink alcohol or who feel uncomfortable around noise and large groups.

Creating cool spaces that serve the whole community involves understanding these dynamics and exploring more inclusive alternatives.

Connecting adaptation efforts

The importance of understanding the dynamics of adaptation efforts is especially relevant when considering children, as they are often more vulnerable to increasing temperatures.

At Felix Road adventure playground – one of the early pilot sites in Bristol – staff introduced shaded areas, drinking water and ice lollies to support children during hot weather.

However, adaptation does not just happen at individual sites, but between them, as connectivity to the playground by foot or public transport exposes children to the heat and traffic.

This highlights that adaptation to heat is a city-wide concern, as the effectiveness of individual cooling interventions can depend on both the space itself and how it can be accessed and used by vulnerable populations.

Buses and trains can become uncomfortably hot, making travel difficult for those most at risk. Our research suggests that for some, staying home might seem safer, but many lack cooling options.

Early discussions in the cool space trial show this is especially true for older adults, who also seek social contact alongside thermal comfort in community centres. Advice to stay home during heatwaves, without adequate cooling or guidance, therefore risks both physical harm and increased social isolation.

Relational approaches to adaptation

Viewing cooling as a social issue transforms how we approach urban adaptation and, more importantly, climate action.

Air conditioning reduces temperature, but it does not help foster trust or strengthen community ties. Our research shows that a well-designed community space, by contrast, integrates physical comfort with social support.

For example, they offer places where a parent can supervise children safely in water play, where an older adult might be offered a cold drink or a fan, or where people can simply rest without judgment. These small interactions, while often overlooked, can contribute to reducing heat stress, dehydration or social isolation during heatwaves, creating public spaces that are safer and more supportive for heat-vulnerable residents.

Cool spaces can also serve multiple roles. A library may host children’s activities or provide food support, while a community centre might offer advice on home cooling.

These spaces show that strong community relationships are key to real climate action, offering comfort, connection and practical help all in one place.

Our research shows that by embedding care into design, cities can build approaches to adaptation that go beyond temperature control, recognising the diverse needs of their communities.

However, to continue serving this role effectively, community spaces require ongoing support, including adequate funding, staffing and resources. Without such support, their ability to provide safe, welcoming and inclusive cooling environments for the most vulnerable can be limited.

Challenges and trade-offs

Our research finds that imagining “cool” adaptation is not without challenges.

Our reflections from the ongoing work in Bristol highlight the importance of context-sensitive, adaptive strategies that consider how people live and their needs and expectations, without neglecting the urgent demands of climate action and health protection.

What works in one neighbourhood may be unsuitable in another – and success cannot be defined solely by temperature reduction or visitor numbers.

Listening to communities, observing patterns of use and being willing to reconsider early designs through experimentation and learning are arguably essential for interventions that are socially, culturally and environmentally appropriate.

Climate change is already reshaping how cities function and how communities think and behave. Heatwaves are no longer rare events; they are increasingly intense and dangerous.

In this context, air conditioning may have a role in specific settings and for specific reasons, but it is not the sole answer. Our research shows it cannot replace locally grounded, inclusive and relational approaches to adaptation.

Bristol’s “cool spaces” initiative demonstrates that interventions are most likely to be effective when they are accessible, welcoming and build community, providing more than just shade or technical relief.

This requires investment, coordination and time, but also a shift in perspective: cooling is not just a technical challenge, but about how we look after one another and how we collectively imagine our public spaces in a changing climate.

The post Guest post: Why cities need more than just air conditioning for extreme heat appeared first on Carbon Brief.