Hydrogen is currently expected to play an important role in society’s energy transition. For the technology to be used on a broad scale, effective hydrogen sensors are required to enable the prevention of flammable oxyhydrogen gas being formed when hydrogen is mixed with air. Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology, in Sweden, have developed what they say is a compact sensor that can be manufactured on a large scale and is well suited to the humid environments where hydrogen is to be found. Unlike existing sensors, the new sensor performs better the more humid it gets.

“The performance of a hydrogen gas sensor can vary dramatically from environment to environment, and humidity is an important factor,” says lead author Athanasios Theodoridis. “An issue today is that many sensors become slower or perform less effectively in humid environments. When we tested our new sensor concept, we discovered that the more we increased the humidity, the stronger the response to hydrogen became. It took us a while to really understand how this could be possible.“

Hydrogen is an increasingly important energy carrier in the transport sector and is used as a raw material in the chemical industry as well as for green steel manufacturing. In addition to water being constantly present in ambient air, it is also formed when hydrogen reacts with oxygen to generate energy. For example, in a fuel cell that can be used in hydrogen-powered vehicles and ships. Furthermore, fuel cells themselves require water to prevent the membranes that separate oxygen and hydrogen inside them from drying out.

Facilities where hydrogen is produced and stored are also constantly in contact with the surrounding air, where humidity varies greatly over time depending on temperature and weather conditions. Therefore, to ensure that the volatile hydrogen gas does not leak and create flammable oxyhydrogen, reliable humidity-tolerant sensors are needed here as well.

The sensor causes the humidity to ‘boil away’

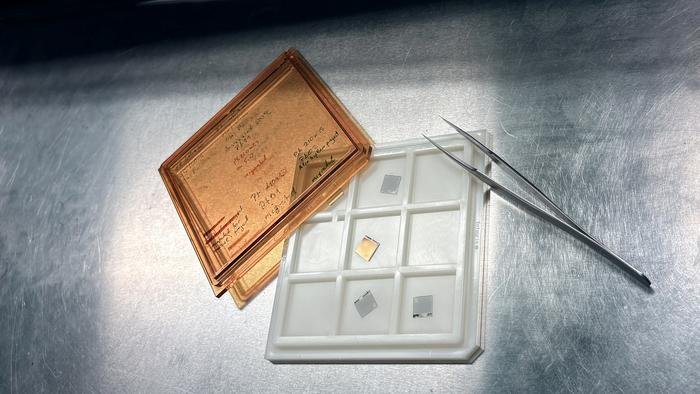

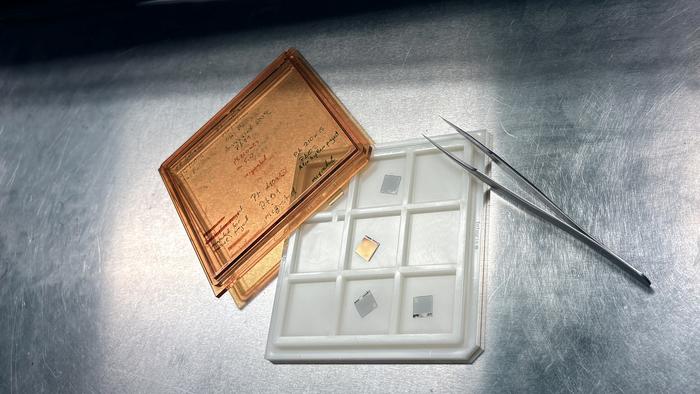

The new humidity-tolerant hydrogen sensor fits on a fingertip and contains tiny particles – nanoparticles – of the metal platinum. The particles act as both catalysts and sensors at the same time. This means that the platinum accelerates the chemical reaction between hydrogen and oxygen from the air, which leads to heat development that causes the humidity, in the form of a film of water on the sensor surface, to ‘boil away’. The amount of hydrogen in the air determines how much of the water film boils away, and the moisture content in the air controls the thickness of the film. It is therefore possible to measure the concentration of hydrogen by measuring the thickness of the water film. And since the thickness of the water film increases as the air becomes more humid, the sensor’s efficiency increases at the same rate. The result of this process can be observed using an optical phenomenon called plasmons, where the platinum nanoparticles capture light and give them a distinct colour. When the concentration of hydrogen gas in the environment changes, the nanoparticles change colour, and at critical levels the sensor triggers an alarm.

The development of plasmonic hydrogen gas sensors has been under way for many years, says the group, which cites breakthroughs made by Professor Christoph Langhammer’s research team in terms of sensor speed and sensitivity, as well as the ability to optimise sensor response and humidity resistance using AI.

Previously, the group based its sensors on nanoparticles of the metal palladium, which absorbs hydrogen in much the same way as a sponge absorbs water. The new platinum-based concept, developed within the framework of the TechForH2 competence centre at Chalmers, has led to what is considered a new type of sensor – a “catalytic plasmonic hydrogen gas sensor” – which opens up new possibilities.

“We tested the sensor for over 140 hours of continuous exposure to humid air. The tests showed that it is stable at various given degrees of humidity and can reliably detect hydrogen gas in these conditions, which is important if it is to be used in real-world environments,” says Athanasios Theodoridis.

The energy transition is placing greater demands on sensors

According to the researchers’ measurements, the sensor detects hydrogen down to 30 ppm, making it one of the world’s most sensitive hydrogen gas sensors in humid environments.

“There is currently strong demand for sensors that perform well in humid environments. As hydrogen plays an increasingly important role in society, there are growing demands for sensors that are not only smaller and more flexible, but also capable of being manufactured on a large scale and at a lower cost. Our new sensor concept satisfies these requirements well,” says Christoph Langhammer, Professor of Physics at Chalmers and one of the founders of the sensor company Insplorion, where he now serves in an advisory capacity.

He also recognises that more than one type of material may be required for future hydrogen gas sensors to function in all types of environments.

“We expect to need to combine different types of active materials to create sensors that perform well regardless of the environment. We now know that certain materials provide speed and sensitivity, while others are better able to withstand humidity. We are now working to apply this knowledge going forward.”

The results of the work have been published in the journal ACS Sensors.