Just 28% of countries have met a UN call to submit new plans on addressing nature loss – a year after the original deadline, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

Several of the world’s most biodiverse countries – including Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Africa – are among those that have not yet released their nature plans.

Countries were asked to submit their pledges, known as national biodiversity strategies and action plans (NBSAPs), by the start of the COP16 biodiversity summit in Colombia on 21 October 2024.

After only 15% of nations met the original deadline, countries agreed at the summit to a new text that “urges” countries to release their NBSAPs “as soon as possible”.

Many developing countries have expressed that a lack of available funding has prevented them from publishing their NBSAPs.

A spokesperson for the Global Environment Facility (Gef), the multilateral fund that provides funding to help with the preparation of NBSAPs, tells Carbon Brief that 120 out of 139 countries that have requested financial support since COP16 have been able to access it.

The spokesperson adds that the UN Environment Programme is “working to resolve outstanding issues” to allow the remaining 19 countries to access financial assistance.

Lack of action

In 2022, nations signed a landmark agreement called the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which aims to halt and reverse nature loss by 2030. It is often described as the “Paris Agreement for nature”.

As part of the agreement, countries agreed to submit new NBSAPs “by” COP16, which began on 21 October 2024 in Cali, Colombia. (Countries failed to find agreement on some key issues in Colombia and met again in Rome, Italy, in February 2025 for a resumed session of COP16.)

NBSAPs are blueprints for how individual countries plan to tackle biodiversity loss and ensure they meet the targets outlined in the GBF.

They are similar to nationally determined contributions (NDCs), the plans that outline how individual countries envisage meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement. However, a key difference is that countries are legally obliged to submit NDCs, but not NBSAPs.

The publishing of new NBSAPs was meant to ensure that countries actually implement the targets of the GBF within their borders.

A lack of implementation was widely cited as one of the major factors behind the failure of the last set of global biodiversity rules, the Aichi targets, which were agreed in 2010.

A joint investigation by Carbon Brief and the Guardian found that 85% of countries missed the UN deadline to submit their NBSAPs by COP16.

At COP16, many countries lamented the lack of NBSAP submissions. At the summit, they agreed to a new text that notes the lack of action and “urges” countries to release their NBSAPs “as soon as possible”.

Now, new Carbon Brief analysis reveals that just 28% of nations (55 of 196 parties) have released their NBSAPs – a year after the deadline.

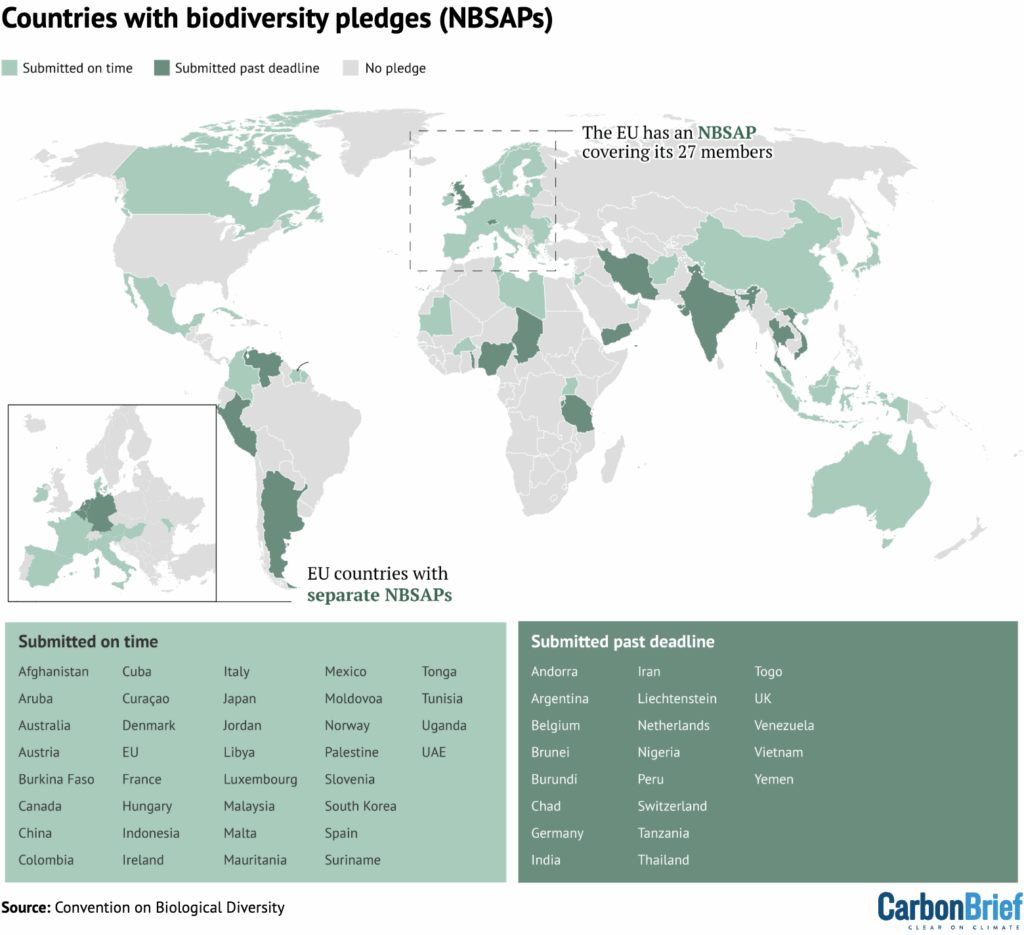

The map below shows countries that submitted their plans to the UN by the 21 October 2024 deadline (light green) and after the deadline (dark green).

Since the original deadline, both Germany and the UK have submitted their NBSAPs. This means that the US, which is not a signatory to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, is now the only G7 nation without a nature plan.

Eight of the “megadiverse countries” – 17 nations that together provide a home to 70% of the world’s biodiversity – are yet to produce their NBSAPs.

This includes Brazil, the world’s most biodiverse nation and host of the upcoming COP30 climate summit.

The other megadiverse countries that have not yet submitted their NBSAPs are the DRC, Ecuador, Madagascar, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, South Africa and the US.

The host of next year’s COP17 biodiversity summit, Armenia, is also among those yet to produce an NBSAP.

According to the GBF and its underlying documents, countries that were “not in a position” to meet the deadline to submit NBSAPs ahead of COP16 were requested to instead submit national targets.

These submissions simply list biodiversity targets that countries will aim for, without an accompanying plan for how they will be achieved.

By the end of the COP16, some 119 parties had produced at least one national target. A year later, this figure has risen to 141, or 72% of countries.

Finance flows

At COP16 in 2024, many developing nations said that a lack of timely funding available from the Gef had prevented them from being able to produce new NBSAPs.

In acknowledgement of this, the NBSAPs text agreed at the summit “requests” the Gef to “provide timely support to all eligible parties, aligned with national circumstances and needs, upon request, to enable them” to release their plans.

A spokesperson for the Gef tells Carbon Brief that 120 out of 139 countries that requested financial support have been able to access it, saying:

“Since 2022, the Gef has approved $123.2m in two tranches to support 139 eligible countries through implementing agencies with their NBSAPs updates or revisions. The 138 countries that requested it had access to a first tranche of support of $44.7m.

“Since October 2024, the second tranche of support has been disbursed by UNDP and UNEP to 120 out of the 139 countries that requested it. UNEP is working to resolve outstanding issues and expedite pending disbursements of the second tranche of support for the remaining 19 countries.”

Panama to Yerevan

Country representatives are currently gathered in Panama City, Panama, for preparatory talks for the next UN biodiversity summit, COP17, which will take place in Yerevan, Armenia, over 19-30 October in 2026.

At COP17, the first global review of nations’ progress to achieving the goals of the GBF is set to take place.

This review will draw from the available NBSAPs, as well as national targets and separate national reports, which are due to be submitted by February 2026.

There is little evidence to suggest that the world is on track to meet the GBF’s mission to halt and reverse biodiversity loss in just five years.

For example, an investigation by Carbon Brief and the Guardian published this year revealed that more than half of nations that have submitted NBSAPs do not commit to the GBF’s flagship target of protecting 30% of land and seas for nature by 2030.

The post Analysis: Just 28% of countries have released nature pledges a year after UN deadline appeared first on Carbon Brief.