Growing tall trees to provide shade for cocoa plantations in west Africa could sequester millions of tonnes of carbon, according to a new study.

The research, published in Nature Sustainability, finds that the additional carbon stored in shade trees, such as banana and palm trees, could entirely “offset” cocoa-related emissions in Ghana and Ivory Coast, without reducing production.

West Africa produces about 60% of the world’s cocoa, which is one of the most emissions-intensive crops to grow.

The authors map the shade provided by trees across cocoa agricultural systems in west Africa, then project how much additional carbon storage would be created by expanding it.

An author of the study tells Carbon Brief that cocoa plantations have been a “big” driver of deforestation and the emissions it causes, but the findings show that there is “huge potential” for cocoa to be “part of the solution”.

Cocoa plantations

Cocoa trees thrive in rainforests, as they need abundant rain, high humidity and stable temperatures. They often grow under the shadow of other plants, such as bananas, plantains and palm trees.

Two countries in west Africa – Ivory Coast and Ghana – dominate global cocoa production and are major exporters to the US and Europe.

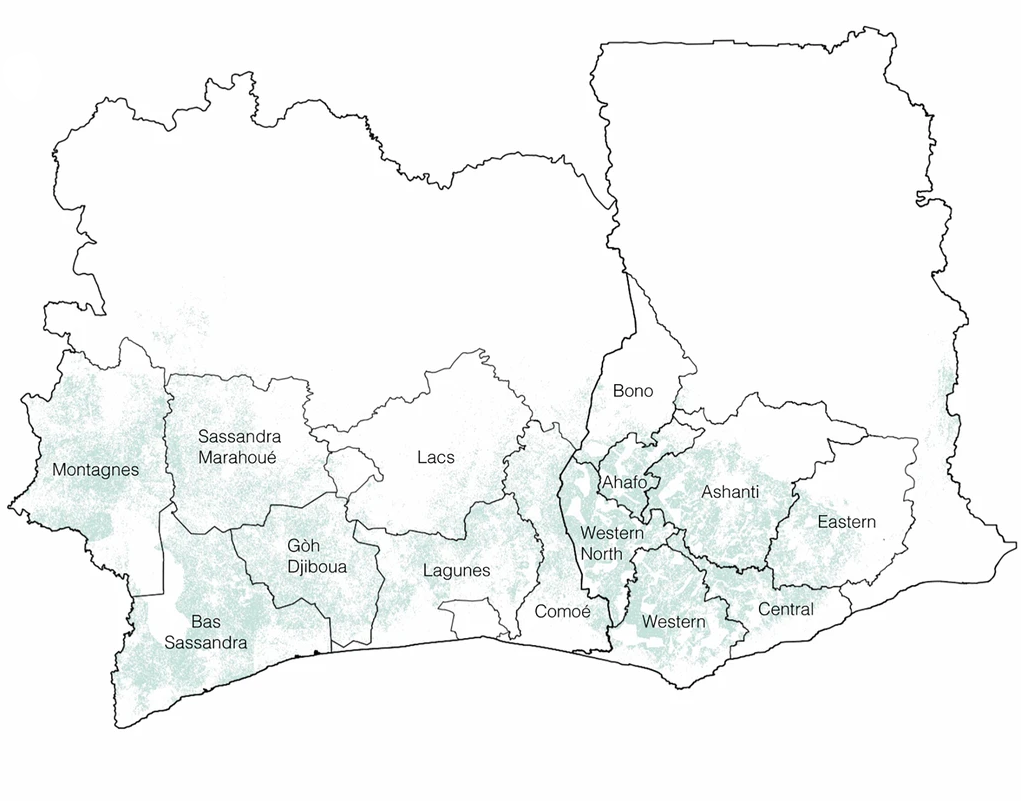

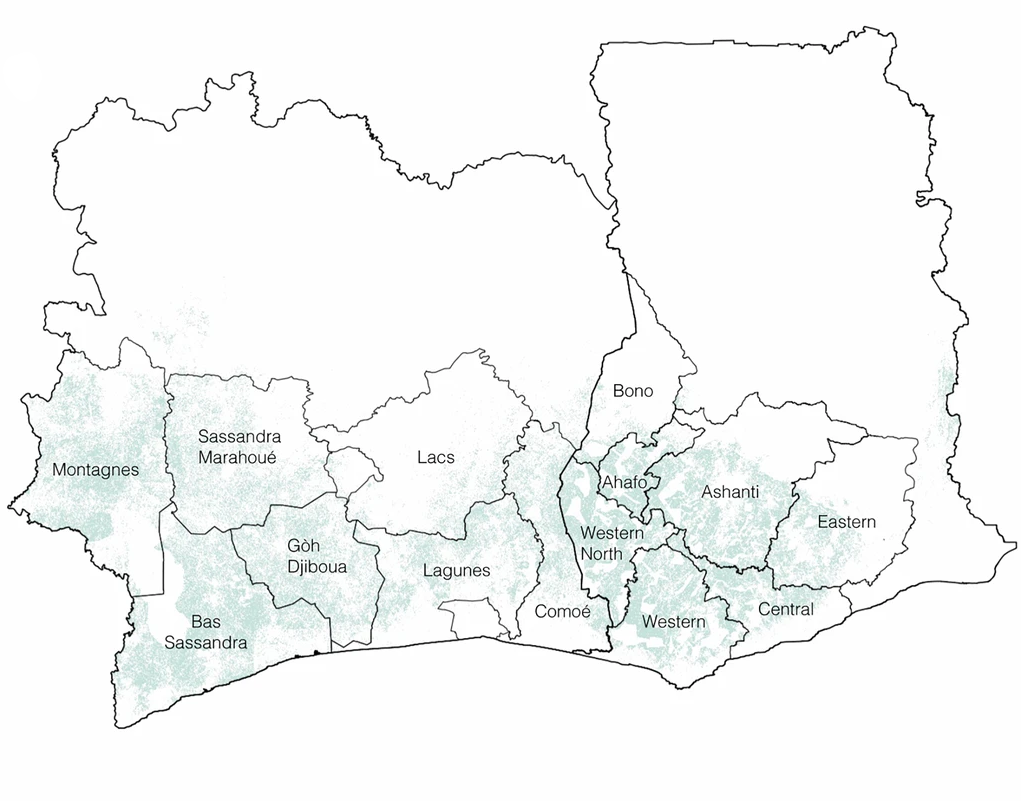

The shading on the map below shows where cocoa is grown in Ivory Coast (left) and Ghana (right).

Both countries have favourable conditions for cocoa production, including tropical forests – which provide nutrients to the soil – a great deal of rain, warm temperatures and low production costs.

Two million farmers in the region rely on cocoa farming for their livelihoods, the study says, and cocoa contributes 10-20% of the two countries’ gross domestic product.

However, cocoa has “one of the most emissions-intensive footprints of all foods”, the study adds.

CO2 equivalent: Greenhouse gases can be expressed in terms of carbon dioxide equivalent, or CO2e. For a given amount, different greenhouse gases trap different amounts of heat in the atmosphere, a quantity known as the global warming potential. Carbon dioxide equivalent is a way of comparing emissions from all greenhouse gases, not just carbon dioxide.

A 2022 study found that producing 1kg of cacao beans in Ivory Coast releases, on average, 1.5kg of CO2-equivalent (CO2e) – largely a result of deforestation. Since 2000, cocoa plantations have driven 37% of forest loss in protected areas in Ivory Coast and 13% of the loss in protected areas in Ghana.

Cocoa plantations cover more than three-and-a-half times as much land as the remaining intact forests in west Africa, according to the study.

Dr Wilma Blaser Hart, a research fellow at the University of Queensland and an author of the study, tells Carbon Brief:

“That land-use change is what makes cocoa such a carbon-intensive product, because there has just been so much forest loss for being able to produce cocoa.”

Shade-grown cocoa crops

Agroforestry is an agricultural method that combines the planting of crops with trees. Agroforestry can raise incomes for farmers and provide ecosystem services, including soil health improvement, biodiversity conservation and carbon sequestration.

The study investigates the amount of carbon that is currently stored in cocoa plantations in Ivory Coast and Ghana, as well as the potential carbon sequestration if agroforestry were expanded in these countries.

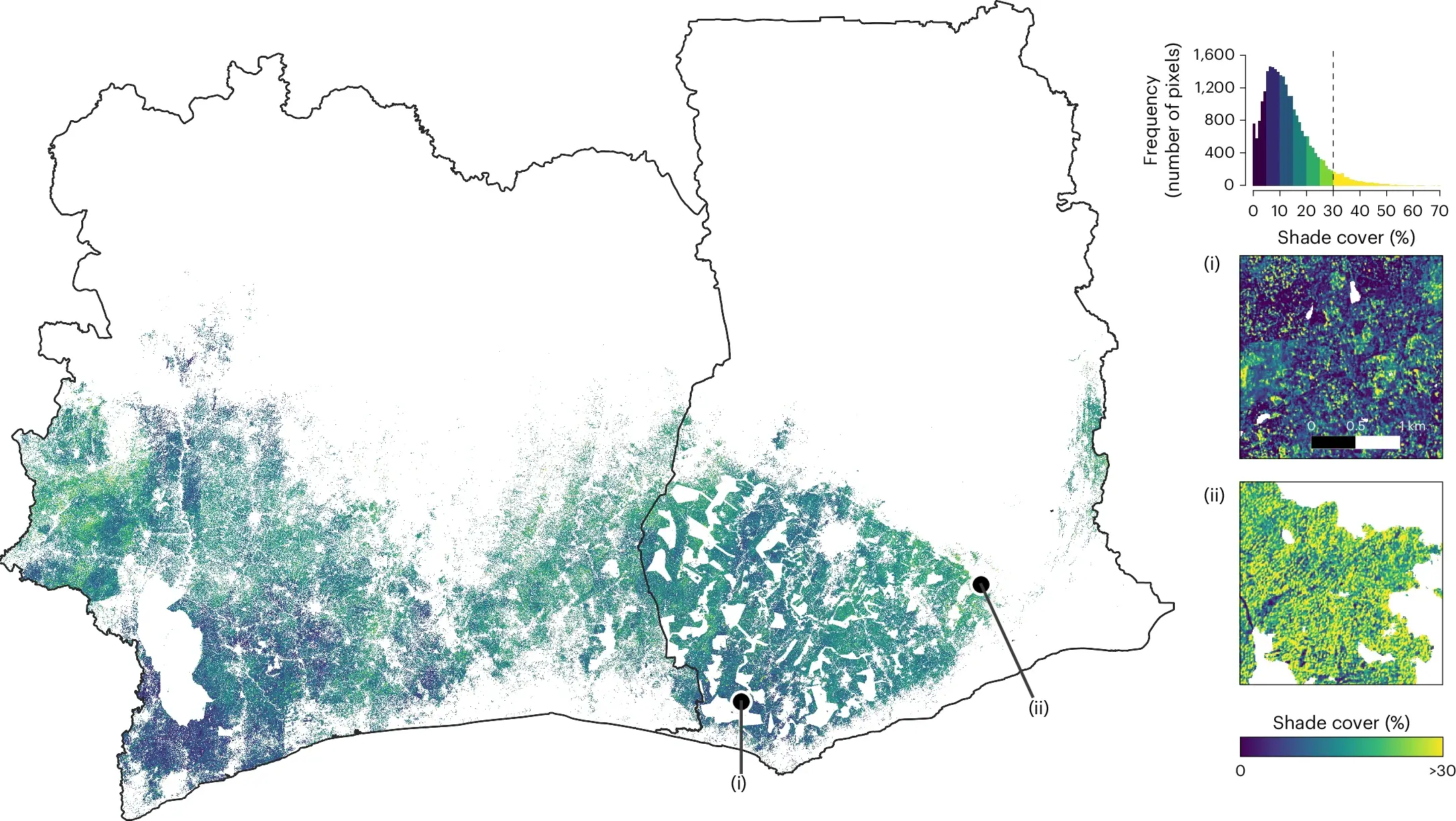

The authors use drones and machine learning to map the cover of shade trees, finding that 13% of the combined area of Ivory Coast and Ghana is currently covered with these trees.

In the study, “shade trees” refers to any trees taller than eight metres – the maximum height of cocoa trees.

The map below shows the area of shade trees in cocoa-growing areas specifically for 2022. The colours indicate levels of tree cover from 0-15% (blue), through to 15-30% (green) and more than 30% (yellow).

The map reveals that cocoa production is “overwhelmingly dominated by full-sun monocultures and low shade-agroforestry”, the study says.

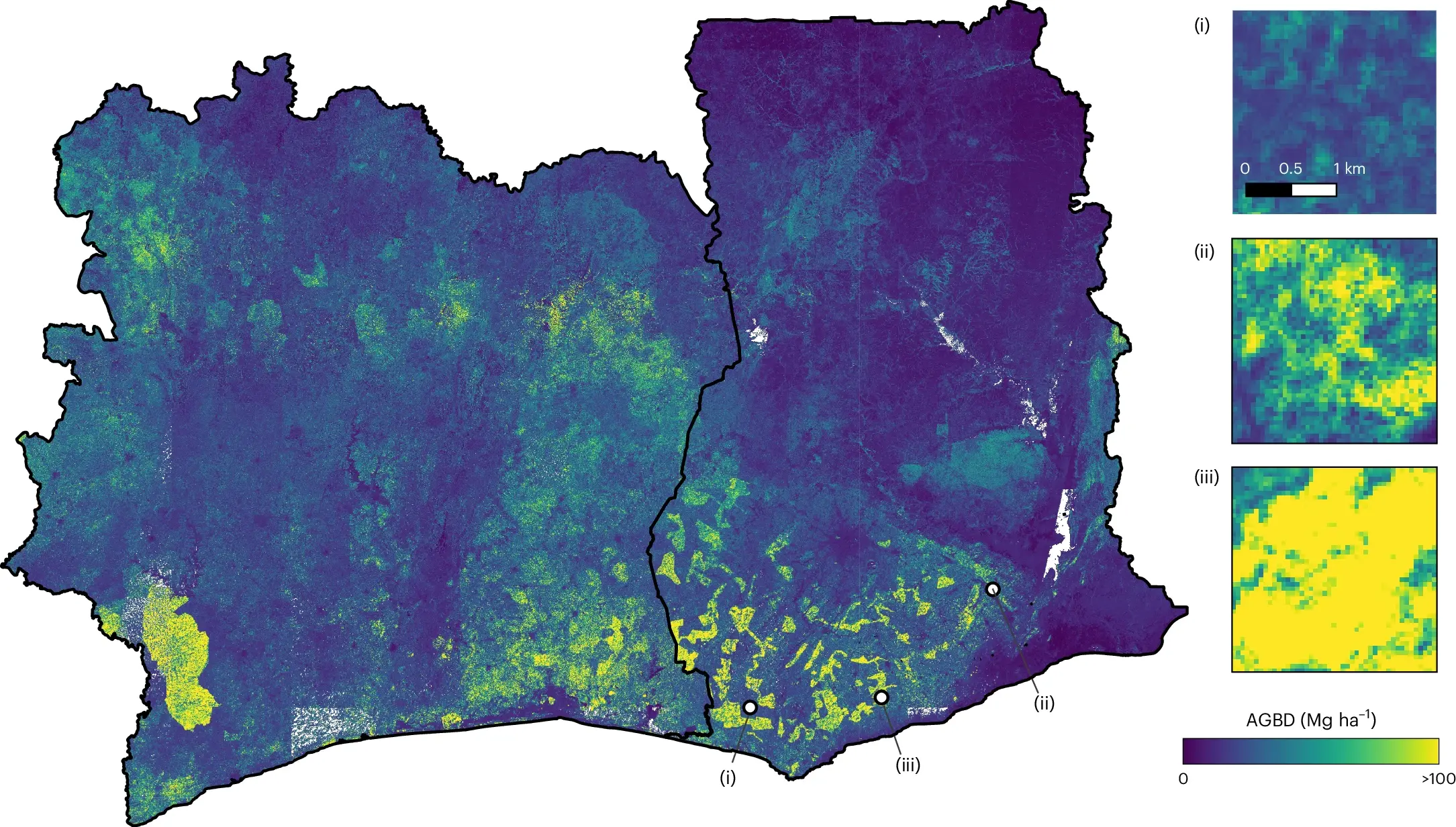

Using satellite data, global maps of tree canopy height and on-ground verification, the researchers map the amount of “aboveground biomass” held by cocoa plantations.

Aboveground biomass comprises all living vegetation that lies above the soil – trees, leaves and other plant matter.

The map below shows the amount of aboveground biomass in both countries. The areas in yellow are those with the highest biomass and, therefore, more stored carbon.

The authors project that if all cocoa plantations increased their cover of shade trees to at least 30%, the additional, taller trees could sequester an “enormous” amount of carbon – 307m tonnes of CO2e (MtCO2e) – enough to fully counterbalance the current cocoa-related emissions in both countries, without reducing production.

Blaser Hart tells Carbon Brief:

“Cocoa itself is a small tree. [It] can grow up to about eight metres tall, so it also sequesters carbon. [But] we found that tall trees that are towering high above cocoa – often timber trees – sequester much more carbon than cocoa.”

In addition, she says, the cover from large trees is “much better for cocoa” since it protects them during the hottest hours of the day, while allowing light through. They also shed large amounts of “litter”, which gets incorporated as organic matter into the soil, sequestering carbon from the atmosphere.

Barriers and limitations

The authors acknowledge several limitations to their study.

For example, they say, the analysis may underestimate the proportion of shade tree cover by excluding trees shorter than eight metres. They also note that the analysis does not consider all of the features of agroforestry systems, such as which species are planted.

Kayeli Laurence is a PhD student of landscape ecology at Jean Lorougnon Guédé University in Ivory Coast and an expert in agroforestry. The researcher, who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief:

“The identified limitations call for caution, particularly when it comes to local, small-scale analyses. However, they do not undermine the general trends highlighted by the study.”

Laurence notes that the study results are consistent with other research highlighting the carbon sequestration potential of agroforestry systems. She says that the projection of carbon sequestration is “ambitious, but credible”. However, she adds:

“In practice, achieving this goal will strongly depend on local conditions: availability of species, technical support, farmers’ willingness and, above all, economic incentives.”

The study also acknowledges that smallholder farmers in west Africa “face several barriers” to adopting agroforestry, including limited incentives and insecure land tenure.

The non-profit scientific research organisation Project Drawdown notes that implementing a certain category of agroforestry called “multistrata” – a combination of long-lasting crops and multiple layers of trees or vegetation – in humid tropical climates would cost more than $1,300 per hectare.

Blaser Hart tells Carbon Brief:

“That’s a huge cost. And it’s not money that farmers have available.”

International landscape

Blaser Hart says that cocoa agroforestry provides further benefits to ecosystems, besides carbon sequestration. These include cooling the air, improving soil fertility and nutrient cycling and providing habitat for wildlife. She adds:

“We’re currently doing a big study on how agroforestry can help to provide habitat for birds. There also seems to be a bit of mammals that use cocoa agroforestry systems. In Ghana, we’re finding quite a bit of genets and civets that are in these systems. From Brazil, there’s a bit of research in the Atlantic Rainforest that shows that some monkeys use them as permanent habitat and others just as corridors to move through.”

Agroforestry is included in the climate commitments of around 40% of developing countries under the Paris Agreement, according to the study.

At the corporate level, the cocoa industry has made commitments to plant “millions of shade trees in agroforests to improve the sustainability of the sector”, the study says.

Blaser Hart tells Carbon Brief that the researchers hope the work will encourage the cocoa industry to better plan its agroforestry interventions, “rather than just haphazardly handing out trees here and there”.

Laurence suggests that policymakers should improve climate finance to support farmers in transitioning to sustainable agricultural systems, while chocolate producers and certification bodies should make stronger commitments to create “real demand for sustainable cocoa produced through agroforestry”.

Ultimately, the study notes that the methods it developed to assess the status of trees in agricultural systems can be used for other commodities grown in agroforests, such as coffee.

The post Growing trees for shade has ‘enormous’ potential for cutting cocoa emissions appeared first on Carbon Brief.