This month marks 10 years since the UK recorded its first named storm.

Storm Abigail struck in November 2015, bringing high winds, lightning and snow and causing power cuts and school closures in northern Scotland.

In the decade that has passed, storm naming has become a key part of how the Met Office warns the public about impending storms.

Storm naming is a public safety tool that makes severe weather easier to remember, talk about and follow.

The success of the scheme offers lessons for how clear communication can help communities prepare, adapt and build resilience in a changing climate.

Here, we look back at a decade of naming storms in the UK and some of the most notable events.

Storms in the UK

Storms in the UK typically take place during the autumn and winter months and last for between two and three days.

The number of named storms varies from year to year. Some storm seasons – for example, 2023–24 – are exceptionally active, while others are much quieter.

The UK owes its stormy climate in large part due to the jet stream – fast-moving winds that blow from west to east high in the atmosphere and push low-pressure weather systems across the Atlantic.

These low-pressure systems can bring heavy rain and strong winds to the UK, which, in turn, causes storms.

Storms in the UK can cause serious damage, felling trees, destroying infrastructure and causing travel disruptions.

Some have resulted in widespread flooding – and others, tragically, in loss of life.

Over the last decade, the UK has seen a number of storms with extreme wind speeds and heavy rainfall.

The table below sets out a list of records set by storms between November 2015 and October 2025.

| Maximum hourly gust speeds | Storm Eunice, 2022 | 122 miles per hour (mph) |

| Highest daily rainfall total | Storm Desmond, 2015 | 264.4mm |

| Lowest mean sea level pressure | Storm Éowyn, 2025 | 941.9 hectopascals (hPa) |

UK storm records for the period November 2015–October 2025. Source: Met Office

Storm naming

Storm naming was introduced in the UK and Ireland at the start of the 2015 storm season.

Launched by the Met Office and Ireland’s weather service, Met Éireann, Dutch weather service the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) joined the storm-naming scheme in 2019.

This collaboration between the UK, Ireland and Netherlands is one of three storm-naming groups in Europe. Each group releases a new alphabetical list of storm names in September.

The graphic below highlights the storm names picked by the Western European storm-naming group for 2025-26.

Not all storms are named. A storm will be named if the Met Office anticipates it having potential to cause disruption or damage.

This is often linked to whether strong winds are expected, but impacts caused by other weather types – for instance, heavy rain, hail or snow – are also considered.

Once named, the storm is referred to consistently by weather services and other authorities in Ireland, Netherlands and the UK.

Storm naming was introduced to improve communication of the weather forecast to the public and help people stay safe during severe weather.

Using a single, authoritative name for a storm allows government and media outlets to deliver a consistent message about approaching severe weather.

In this way, the public will be better placed to keep themselves, their homes and businesses safe.

There have typically been around half a dozen named storms each year since November 2015, although this varies on a year-to-year basis.

The 2023-24 storm season saw the most named storms to date. In August 2024, Storm Lillian became the 12th named storm of that season.

Below is a table of all the storms that have been named since 2015.

Storms named between November 2015 and October 2025. Source: Met Office.

Notable named storms

While every year since the scheme began has seen storms strong enough to be named, some storms have been particularly significant.

Storm Desmond, December 2015

Storm Desmond brought extreme rainfall to north-west England. The weather station in Honister Pass in Cumbria recorded 34.1cm of rainfall in just 24 hours in a new UK record. Another record was set when 405mm of rain fell at Thirlmere in Cumbria over two consecutive days.

The subsequent floods affected thousands of homes and businesses across Cumbria and other parts of northern England, sweeping away several bridges and cutting road and rail links.

Storm Desmond led to the government launching the National Flood Resilience Review.

Storm Arwen, November 2021

Storm Arwen is an example of how the damages caused by a storm depends on more than its overall strength. A storm’s location, duration and wind direction also plays a role.

This storm occurred after an area of pressure in the North Sea drove very strong northerly winds across north-eastern parts of the UK. Winds gusted at up to 98mph at Brizlee Wood in Northumberland.

The unusual wind direction of Storm Arwen resulted in the felling of thousands of trees and left more than a million homes without power. Parts of the Pennines also saw significant disruption from lying snow.

Storms, like Arwen, that have a wind direction different to the prevailing south-westerly direction are less frequent, but are nevertheless a key part of the UK’s climate.

Storm Eunice, February 2022

In February 2022, three named storms affected the UK within the space of a week. The second of these storms was Storm Eunice.

Storms in close succession can cause particular problems because clean-up efforts can be hampered by further severe weather.

Storm Eunice was the most severe and damaging storm to affect England and Wales since February 2014. Gusts reached 122mph at Needles on the Isle of Wight – the highest on record for England at a low-level station.

The storm caused deaths, widespread damage to buildings and major travel disruption, including the temporary closure of the Port of Dover.

Storm Babet, October 2023

Storm Babet was notable for prolonged and intense rainfall which led to severe flooding, evacuations and sadly, deaths. In eastern Scotland, particularly in the county of Angus, rainfall totals reached 150-200mm, with some areas experiencing their wettest day on record since 1891.

A key factor with this storm was its unusual track, or path. The storm moved south to north, picking up additional moisture as it crossed the Bay of Biscay. A high-pressure “blocking” weather system over Scandinavia prevented Babet clearing the UK eastwards into the North Sea. As a result, high wind speeds were sustained across north-east England and much of Scotland for a prolonged period.

Storm Éowyn, January 2025

Storm Éowyn was the UK’s most powerful windstorm in more than decade, with the brunt of impacts felt in Northern Ireland and Scotland’s populous Central Belt.

Gusts exceeded 90mph in Northern Ireland – where this was the most severe wind storm since 1998 – while a 100mph gust was recorded at Drumalbin in Lanarkshire.

Roads were closed, flights, ferries and trains were cancelled and more than a million homes were reported to be without power at the peak of the storm. Scotland’s national botanical collection at the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh saw several dozen felled or badly damaged trees.

Storm Éowyn’s intensity and geographic reach made it a standout event in recent years.

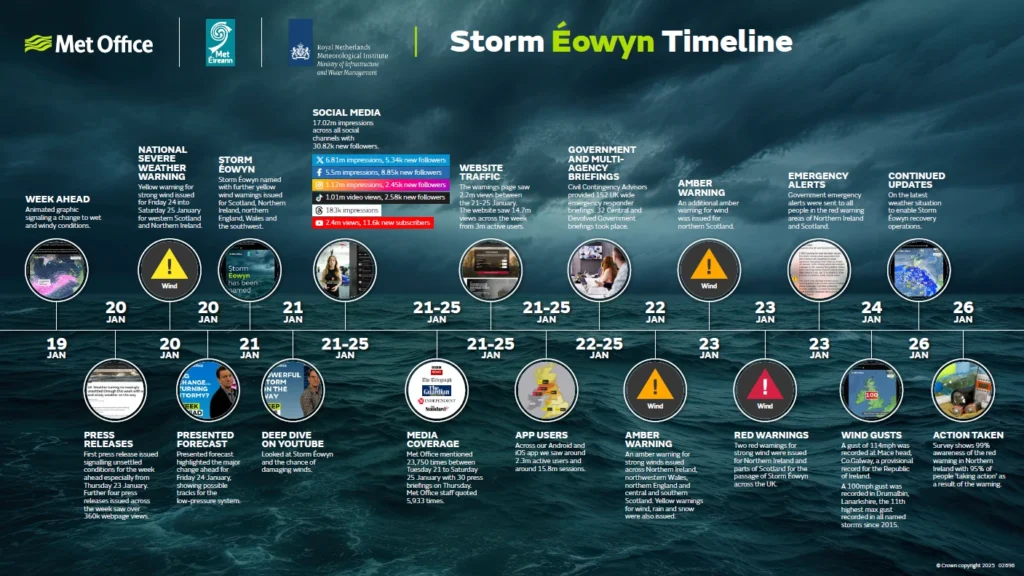

The timeline below shows how the Met Office worked with Met Éireann and KNMI to alert the public about Storm Éowyn.

Climate change and storms

There is no evidence of positive or negative trends in windstorm number or intensity in the UK’s recent climate.

Trends in windstorm frequency are difficult to detect, because numbers vary year-to-year and decade-to-decade.

Most climate projections indicate that winter windstorms will increase slightly in number and intensity over the UK, including disproportionately more severe storms. However, scientists have “medium confidence” in these projections – because a few climate models indicate differently.

This uncertainty highlights the need for ongoing research into how climate change may influence the severity and frequency of windstorms in northern Europe.

On the other hand, scientists are confident that climate change is making rainfall during storms more intense.

A 2024 attribution study involving Met Office scientists showed that climate change has made rainfall during storms more intense through autumn and winter in the UK. The researchers noted that this trend is set to increase as the planet warms.

Recent increases in flooding in the UK have also been linked to climate change.

Other research, meanwhile, has found that sea level rise caused by climate change will worsen storm surges and high waves during windstorms.

The continuing unpredictability of UK storms – combined with projections of increased rainfall and heightened coastal damage under climate change – means that being prepared for, and adapting to, the future weather is crucial.

The post Met Office: Ten years of naming UK storms to warn the public appeared first on Carbon Brief.