Proposals to build coal-fired plants in China reached a record high in 2025, finds a new study.

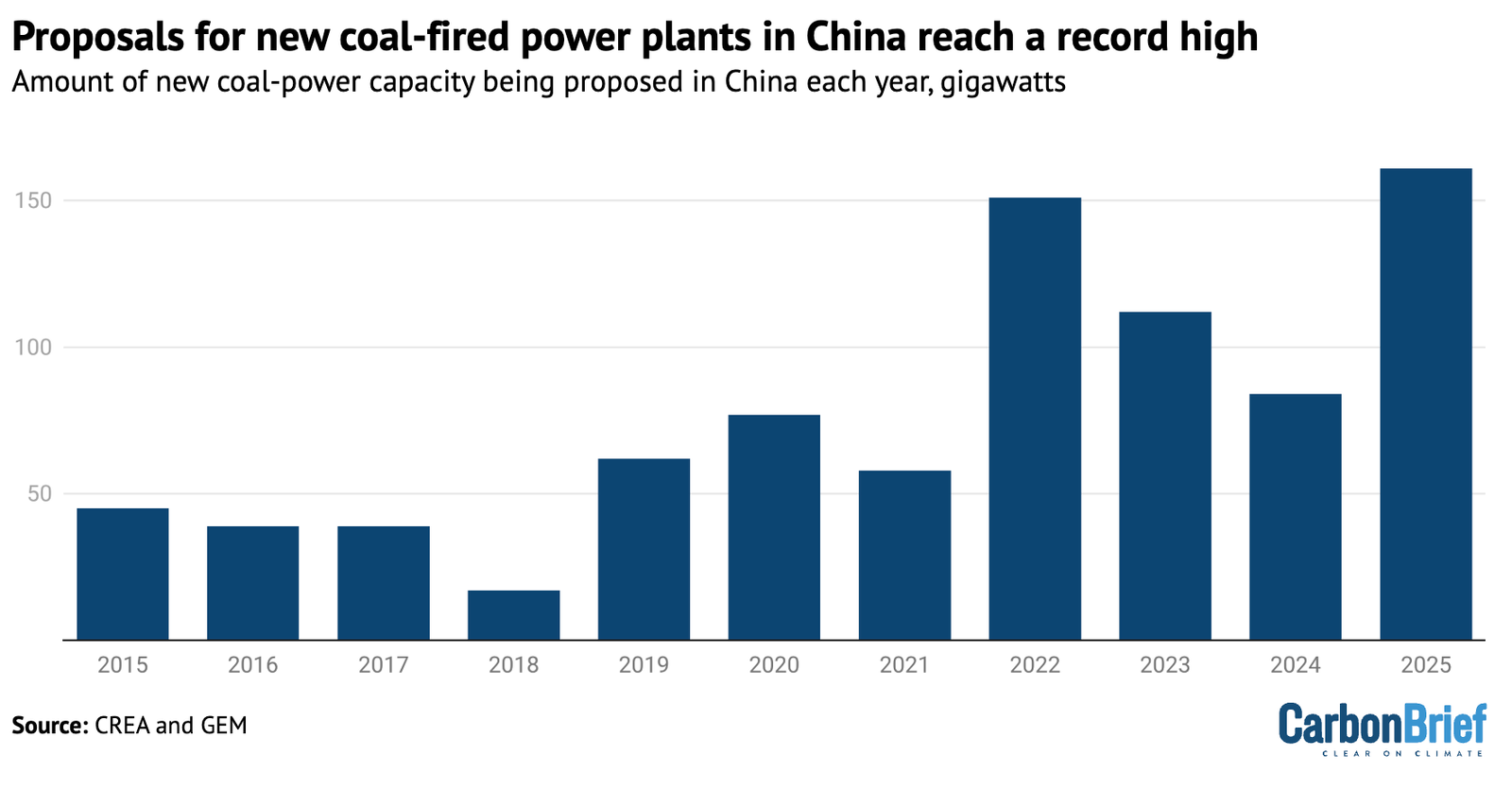

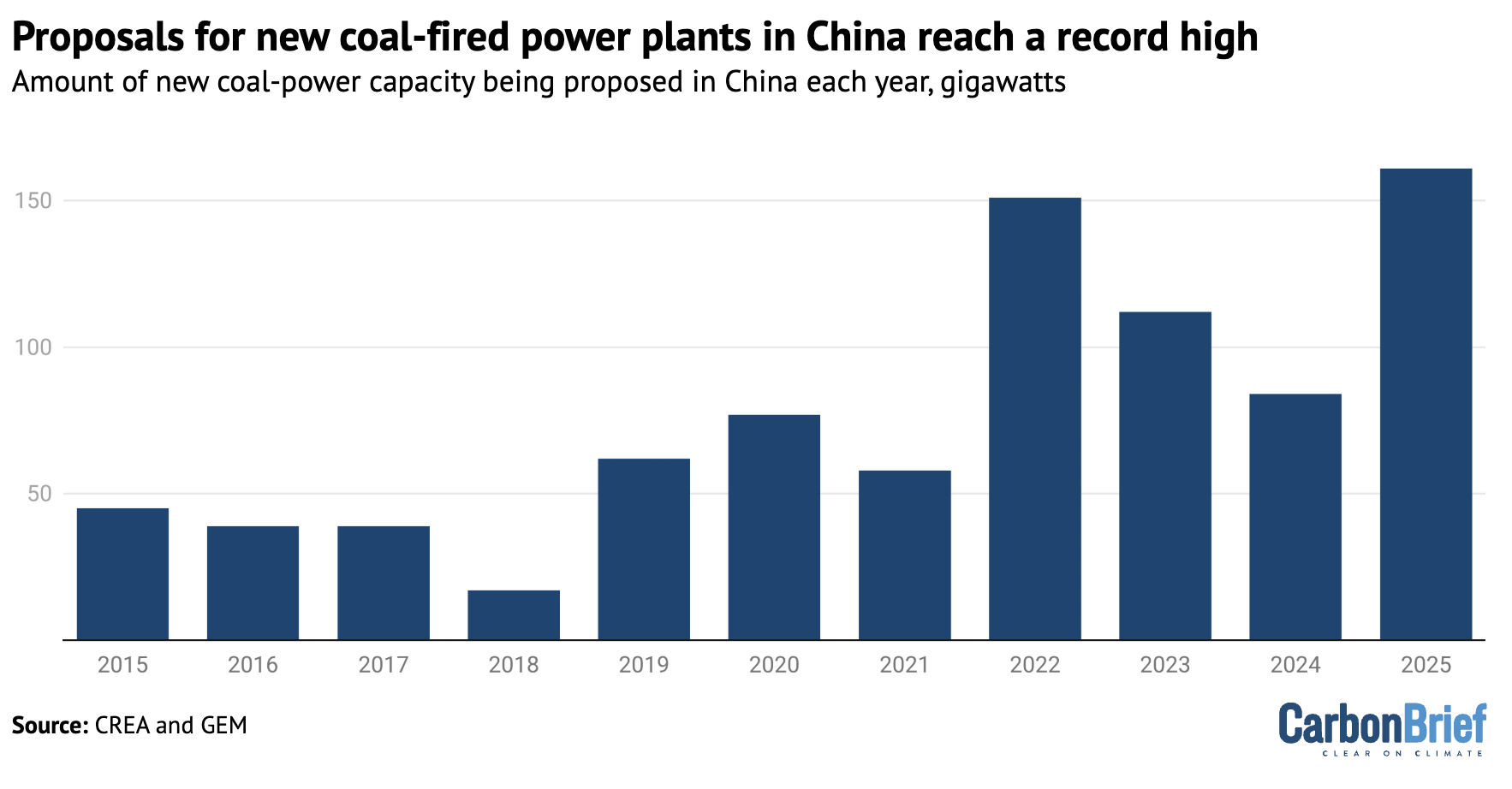

The report, released by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) and Global Energy Monitor (GEM), says that, in 2025, developers submitted new or reactivated proposals to build a total of 161 gigawatts (GW) of new coal-fired power plants.

The new proposals come even as China’s buildout of renewable energy pushed down coal-power generation and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in 2025, meaning many coal plants are already running at just half of their maximum capacity.

The co-authors argue that while clean-energy growth may limit emissions from coal power in the short term, the surge in proposals could lock in new coal assets, “weaken…incentives” for power-system reform and help keep coal capacity online in spite of China’s climate goals.

The high rate of new proposals, the study says, likely reflects a “rush by the coal industry stakeholders” to develop projects before an expected tightening of climate policy in the next five years.

In addition, “misaligned” payment mechanisms are encouraging developers to propose large-scale coal units, which – if developed – could impact the transition of the coal sector from playing the central role in electricity generation to flexibly supporting a system built on clean power.

Significant additions pushing down running hours

The report finds that the amount of new coal-fired power proposals by Chinese developers, including reactivated applications, hit a new peak in 2025, at 161GW. This is equal to 13% of the coal capacity currently online in China.

The country is continuing to add significant coal-power capacity, with a record 95GW added to the grid last year and another 291GW in the pipeline – meaning units that have been proposed, are actively under construction or have already been permitted.

Moreover, around two-thirds of coal-power capacity proposed in China since 2014 has either been commissioned – meaning it has been completed and started operating – or remains in the pipeline, Christine Shearer, report co-author and research analyst at thinktank Global Energy Monitor, tells Carbon Brief.

She adds that this is the “reverse of what we see outside China, where roughly two-thirds of proposed coal capacity never makes it to construction”.

Coal remains a significant part of China’s power mix, making the nation’s electricity sector one of the world’s largest emitters. Indeed, the power sector emitted more than 5.6bn tonnes of carbon dioxide (GtCO2) in 2024 – meaning that if it were its own country, it would have the highest emissions of any country except China itself.

But emissions from the power sector have been flat or falling since March 2024, according to analysis for Carbon Brief by CREA lead analyst Lauri Myllyvirta.

This is largely due to China’s rapid installation of renewable power, which is covering nearly all of new electricity demand and pushing coal generation into decline in 2025.

Some parts of the coal-power pipeline are reflecting this shift. In 2025, construction began on 83GW of new coal capacity – down from 98GW in 2024.

In addition, new permitting fell to a four-year low, at 45GW, which could point to tighter controls on coal-plant approvals in the future, says the report.

The chart below shows the amount of new coal-power capacity being proposed in China each year, in GW.

The shift from new power demand being met by coal to being met by renewable energy means any “additional coal power capacity would face structurally low utilisation”, the report says, referring to the number of hours that plants are able to operate each year.

This reduces coal-plant earnings needed to cover the cost of investment and makes instances of “stranded [coal] assets and compensation pressures” more likely.

A previous analysis for Carbon Brief finds that “larger additions of coal capacity are often followed by falling utilisation” – meaning that the construction of new coal plants does not necessarily increase emissions.

Utilisation rates for coal-fired power plants have hovered around 51% since 2025, according to the CREA and GEM report.

Shearer argues that while low utilisation rates would “dampen the immediate impact on annual CO2 emissions”, in the long-term the buildout “locks capital into fossil fuels” and “weakens incentives to build the cleaner forms of flexibility” needed for a renewables-centred system.

Low utilisation has also not led to coal plant capacity being retired in any notable way, the report notes, with generators instead supported by the coal “capacity payment” mechanism and extending the life of older units.

Delayed retirement of older coal plants causes “persistent overcapacity” and adds to calls for further compensation and policy support, the report says.

Coal generation has “no room to expand” under China’s international climate pledge for 2030, it adds, with utilisation rates for coal units likely to fall to 42% if renewables continue to meet all additional demand and if all of the plants currently under construction or permitted are brought online.

Crunch-time for coal

The surge in new proposals reflects a “rush” by the coal industry to ensure their projects are approved before the policy environment tightens, according to the report.

China is expected to introduce absolute emissions targets over the next five years. While these are expected to be aspirational for the first five years – alongside binding targets for carbon intensity, the emissions per unit of GDP – from 2030 they will be binding.

The current five-year period until 2030 will also likely see most of China’s energy-intensive industries pulled into the scope of its national carbon market.

In the power sector, government officials have said that coal is expected to shift from playing a major role in power supply to supporting “flexibility” operations.

This would require coal plants to shift between varying load levels and respond quickly to changes in demand and other system needs.

However, the report finds, the approvals for coal power “continue to reflect expectations of high operating hours”, instead of flexible operations.

For many of these proposals, planned annual utilisation was stated to be more than 4,800 hours, or 55% of hours in the year. This is greater than the 4,685 utilisation hours (53%) logged in 2023, the year in which the most coal power was generated over the past decade, according to data shared by the report authors with Carbon Brief.

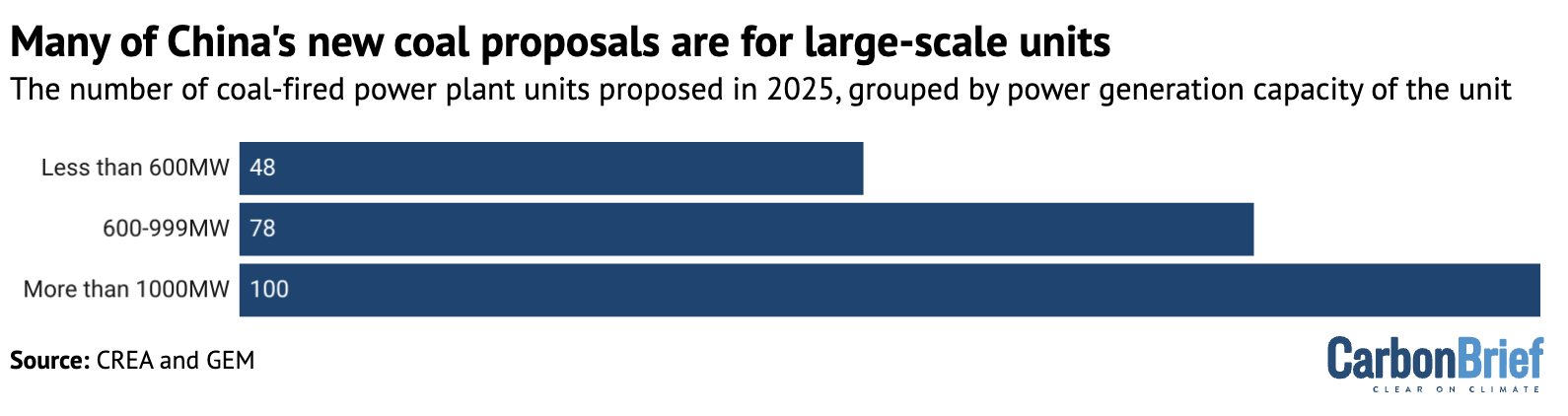

In addition, the report says that many of the new coal-power proposals in 2025 were for “large-scale units”, each representing at least 1GW of power, as shown in the figure below.

These larger units are designed for “stable, continuous operation” and are “poorly suited to the type of flexibility increasingly required in a power system dominated by wind and solar”, says the report.

This suggests that “project developers still anticipated base-load style operation”, it adds, “sitting uneasily” with the fact of higher clean-energy generation and falling coal plant utilisation.

Reliance on sales and subsidies

This persistence in developing large-scale units could be explained by the financial incentives that govern the coal-power industry.

Coal power plants are cheap to build but risk low profits and high costs, with many current operators already facing losses at recent utilisation rates.

In 2024, the government established a capacity payment mechanism for coal-fired power plants. This mechanism rewards developers for adding “seldom-utilised, backup” capacity to the grid.

These capacity payments, as well as regulated pricing and implicit government backing “can make plants viable on paper even if utilisation and operating margins are weak”, Shearer tells Carbon Brief, which may explain the continued appetite for new coal from developers.

More than 100bn yuan ($14bn) in capacity payments were made to coal plants in 2024, although it has not yet had a discernable impact on utilisation.

Large-scale units, the report says, are “particularly well positioned” to benefit from the policy, as it rewards maximising capacity and does not favour plants that are more suited for flexible operations.

(The Chinese government recently announced plans to adjust the mechanism, confirming that in some cases capacity payments could be more than the initial expected threshold of 50% of a benchmark coal plant’s total fixed costs.)

Meanwhile, the report adds that coal-fired power plants continue to earn most of their revenue from selling electricity, with only 5% of total income coming from capacity payments.

As such, these “misaligned incentives” encourage producing power and installing significant new capacity, despite the government’s aim to shift coal to a supporting role in the system.

Shearer tells Carbon Brief that a better approach to flexibility would be to “adopt technology-neutral flexibility standards”, rather than focusing on “flexible coal”, which would mean coal would have to “compete directly with storage, demand response, grid upgrades and other clean options”. She adds:

“The risk of coal-specific flexibility policies is that they lock in capacity rather than solve the underlying system need.”

The post ‘Rush’ for new coal in China hits record high in 2025 as climate deadline looms appeared first on Carbon Brief.